Country

Assessment

Article 51 on fines in the Regulation on Petroleum Operations, 2009 , includes provisions on applicable monetary fines. If a monetary correction is needed, the penalty must be assessed under the terms of the Tax Correction Unit in force.

No evidence regarding nonmonetary penalties could be found in the sources consulted.

No evidence regarding performance requirements could be found in the sources consulted.

The Angola Liquefied Natural Gas Project (ALNG) is the first LNG project in Angola. It uses associated natural gas, helping to reduce gas flaring and associated greenhouse gas emissions. Daily capacity is 1.1 billion cubic feet (bcf). Decree 10/2007 created a special legal regime for the ALNG that includes specific maritime, tax, customs, and foreign exchange regimes. The ALNG is subject to a specific tax regime under which sponsor entities hold a tax credit of 144 months starting from the date of initial commercial production, deductible against the profit income tax. The ALNG is subject to a quarterly gas tax from the first LNG export shipment date. Decree 7/2018 provides more attractive tax rates to gas operations. The gas production tax is 5 percent (compared with 10 percent for oil).

PSCs state that any surplus gas produced by oil companies that is not used for field use must be given free of charge to Sonangol (see section 5 of this chapter). The capital expenditures borne by companies for the storage and delivery of associated gas to Sonangol are cost recoverable. Sonangol will manage the gas infrastructure once commissioned and will also bear the cost of operating it. Should funding the gas infrastructure have a significant negative impact on the economic conditions agreed to in the PSCs for the contractor, Sonangol is required to modify the economic terms of the contract to restore the contractor’s economic position before the gas infrastructure project.

No evidence regarding the use of market-based principles to reduce flaring, venting, or associated emissions could be found in the sources consulted.

The fact that midstream licenses do not provide open access rights to third parties in privately constructed infrastructure could be a barrier to the commercialization of associated gas. These licenses are typically granted to companies affiliated with Sonangol. Third parties do not have access to such infrastructure if the right-of-way has already been granted for the midstream license.

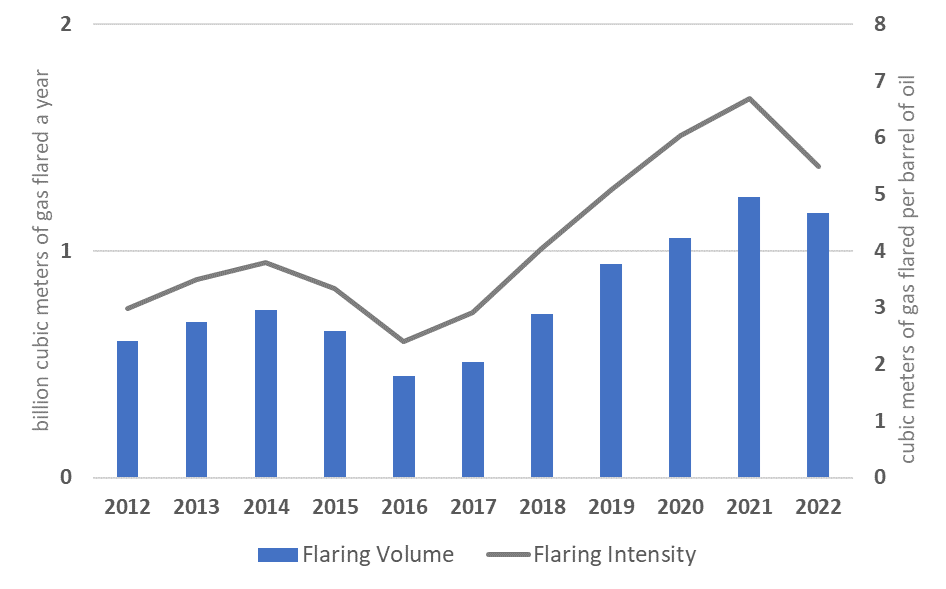

The volume of gas flared in Argentina doubled from 0.6 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2012 to 1.2 bcm in 2022 (Figure 1). During this period, oil production varied by about 10 percent with a significant uptick to 583,000 barrels a day in 2022. After broadly stabilizing in the first half of the 2010s, the flaring intensity increased steadily after 2017, reaching the highest level in 2021 and dropping again slightly in 2022. There were 156 individual flare sites in the most recent flare count, conducted in 2022.

Figure 1. Gas flaring volume and intensity in Argentina, 2012–22

Argentina participates in the Global Methane Initiative (n.d.) and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition. It submitted its first NDC in 2016 and its second in 2020. In its second NDC, Argentina committed not to exceed net emissions of 359 million tCO2e by 2030. This new goal is 26 percent lower than the target in the 2016 NDC. It represents an emissions reduction of 19 percent by 2030 from the 2007 peak emissions level.

Argentina participates in the Global Methane Initiative, the Global Methane Pledge, and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition. It submitted its first NDC in 2016 and its second in 2020. In its second NDC, Argentina committed not to exceed net emissions of 359 million tCO2e by 2030. At the end of 2021, Argentina updated its second NDC target to 349 million tCO2e by 2030. This new goal is 27.7 percent lower than the target in the 2016 NDC. It represents an emissions reduction of 21 percent by 2030 from the 2007 peak emissions level. The NDC does not specifically mention gas flaring or venting.

Most of Argentina’s oil and gas production is in Patagonia. The province of Chubut produces most of the oil. About half of the country’s natural gas comes from the Neuquén Basin, which is home to unconventional reserves, including the Vaca Muerta formation, which stretches across four provinces: Neuquén, La Pampa, Mendoza, and Rio Negro.

Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF) is the country’s largest producer of oil and gas. In the 1990s, 80 percent of YPF was privatized. YPF relinquished some upstream areas and entered into joint ventures with private operators for its most productive blocks. The state subsequently sold its remaining 20 percent stake to the Spanish oil company Repsol. However, the government retained veto power over crucial decisions.

In the gas sector, another state-owned company, Gas del Estado, was also privatized and unbundled into two gas transport and eight gas distribution companies. In 2012, through Law 26.741, 2012, the government expropriated a 51 percent controlling stake in YPF. Subsequently, the government promoted public-private partnerships with the renationalized YPF, with the primary goal of addressing Argentina’s energy shortages.

YPF committed itself to reducing its carbon dioxide emissions intensity by 10 percent by 2023. It will achieve this reduction through more efficient energy management, reductions in flared and vented gas, electrification and digitization of its operations, and adoption of low-carbon energy sources.

Gas flaring and venting are regulated at the federal and provincial levels. The federal regulatory authority is the Undersecretariat of Hydrocarbons (Subsecretaría de Hidrocarburos), part of the Federal Energy Secretariat (Secretaría de Gobierno de Energía). The federal regulatory authority for natural gas is the Energy Secretariat. Decree No. 7/2019 created the Ministry of Productive Development and placed the Energy Secretariat under its authority.

Each oil- and gas-producing province has its own regulator, governed by the Hydrocarbons Law, 1967 , and by provincial legislation and regulations. The regulatory authority is the Undersecretariat of Energy, Mining and Hydrocarbons, under the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources in Neuquén, the Ministry of Hydrocarbons in Chubut, the Energy Institute in Santa Cruz, and the Energy Secretariat in Rio Negro.

Resolution No. 143/1998 prescribes that gas be flared, not vented, through appropriate procedures. If, for technical reasons, the gas cannot be flared, the operator is required to submit a report to justify venting.

Annex 1 (“Norms and Procedures for Venting Gas”) lists the circumstances under which gas venting is allowed:

- section 3.1 permits flaring or venting when the gas-to-oil ratio at the vent point does not exceed 1 m³ of gas per 1 m³ of crude oil produced.

- section 4.4 permits periodic venting of gas when there are no conduction lines to capture the gas at the wellhead.

- section 5.1 permits venting when it occurs during well testing.

The authorities should be notified in writing of all flaring and venting for all causes (maintenance, operations, or emergencies) within 24 hours. The reasons for the contingency, flow rates and damages, and the immediate measures and corrective measures implemented must be detailed.

The Neuquén province’s Law 2.175/1997 prohibits gaseous emissions from oil and gas wells. Emissions from flares can be authorized for oil wells if the emissions are not characterized as a hazardous waste. Article 2 of Neuquén Provincial Decree No. 29/2001 requires the operator to submit a report documenting a justification for venting if the unused gas cannot be flared for technical reasons and to follow the same criteria for venting as stipulated in Resolution No. 143/1998.

Article 4 of Resolution No. 143/1998 requires the operator to submit a request for exemption to the undersecretary for breaching the permitted limits. Annex 1 of the resolution describes the procedure for submitting such a request. The regulator has 90 days from the date of receipt of the request to issue the approval or rejection of the request. Every request for an exemption must demonstrate for each reservoir the technical reasons for exceeding the limits and the maximum flow rate of gas to be flared or vented. The documentation and data should be updated every six months by May 31 and November 30 of each year in which exemptions are requested.

Section 3 of Annex 1 of Resolution No. 143/1998 states that the Energy Secretariat may judge whether venting should be reduced, either temporarily or permanently, on a case-by-case basis. Section 3 requires allowed venting to follow appropriate procedures and minimize the emissions of harmful gases into the environment. Section 3 also states that Sections 3, 4, and 5 of Resolution No. 105 should be followed in all cases. The Neuquén province’s Decree No. 29/2001 outlines the same criteria as Resolution No. 143/1998.