Policy and Targets

Background and the Role of Reductions in Meeting Environmental and Economic Objectives

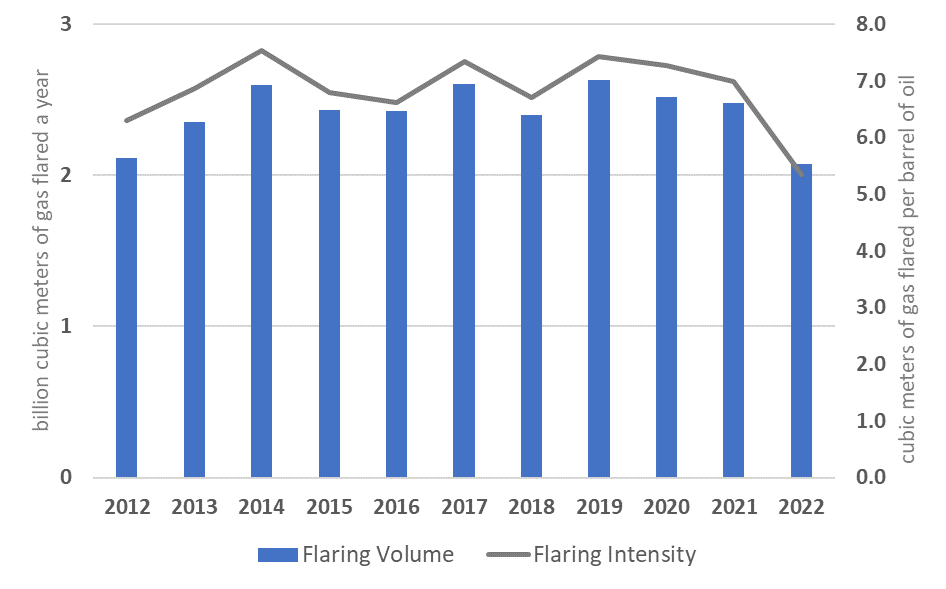

Between 2012 and 2022, oil production in Oman was fairly stable, varying by around 5 percent from the mean. Flaring volumes, however, dropped by 15 percent, most of which between 2021 and 2022, and the flaring intensity dropped by 2 percent over the same period (Figure 10). There were 111 individual flare sites in the most recent flare count, conducted in 2022.

Figure 10 Gas flaring volume and intensity in Oman, 2012–22

In 2017, Oman endorsed the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 initiative; in 2017, the Petroleum Development Oman (PDO) did so. Oman submitted its second Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in July 2021. It commits the government to an unconditional contribution of a 3 percent reduction in the growth of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030 and a conditional contribution of an additional 4 percent reduction, for a total of 7 percent. The upstream oil and gas sector targets zero emissions by 2050. One instrument for implementing this target is the 2016 endorsement of the Zero Routine Flaring initiative. The second NDC also outlines measures that will reduce the GHG intensity of upstream oil and gas operations: electrification of equipment, reliance on renewable energy for electricity, efficiency improvement in existing facilities, and a significant reduction in gas flaring as well as methane and other fugitive emissions. Operators in Oman have used the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) of the UNFCCC for two associated gas-recovery projects. Oman participates in the Global Methane Pledge.

The PDO is responsible for producing about 70 percent of oil and gas in Oman. Since endorsing the Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 initiative, the Ministry of Oil and Gas, now called the Ministry of Energy and Minerals, has led efforts to develop flaring and venting guidelines. At the same time, the PDO and other operators have implemented projects to reduce flaring. The government issued 28 royal decrees in August 2020. The Ministry of Oil and Gas was renamed the Ministry of Energy and Minerals (MEM), and the Environment Authority was created to replace the Ministry of Environment and Climate Affairs. The Financial Affairs and Energy Resources Council, which used to set domestic oil and gas prices, was abolished. Apart from these decrees, there were parallel changes in the energy sector. At the end of 2019, a new national petroleum investment company, OQ, was formed by merging nine companies across the energy sector. At the end of 2020, a new government company, Energy Development Oman, was established. This holding company of the PDO will focus on natural gas, renewable energy, and green hydrogen.

Targets and Limits

There are no targets or limits on the volumes of natural gas flared or vented. However, regulations are under development, which are expected to include targets.

Legal, Regulatory Framework, and Contractual rights

Primary and Secondary Legislation and Regulation

Articles 39 and 40 of Royal Decree No. 8/2011, known as the Oil and Gas Law, set out environmental protection principles. According to Article 39, operators should not dispose of gas unless necessary, and when necessary, they should use appropriate means to protect the environment. Article 39 also requires operators to reduce GHG emissions by using appropriate technology. Article 40 requires the use of international best practices, standards, and specifications. Article 18 requires that concessionaires and their subcontractors comply with the terms of the concession agreement and all permits and approvals issued by the MEM or other government authorities, as well as with other laws, rules, and regulations in Oman.

Exploration and production-sharing agreements include health, safety, and environment clauses that reflect existing laws and current energy and environment policies. For example, exploration and production-sharing agreements ban flaring without a permit except during well testing. Ministerial Decree No. 14/2012, known as the Well Test Regulatory Protocol, specifies the requirements for operators to obtain a permit.

Ministerial Decision No. 118/2004, entitled the Regulations for Air Pollution Control from Stationary Sources, outlines regulations for air emissions from stationary sources. Article 7 provides the guidelines for obtaining a permit. Permits are valid for three years but can be renewed for a similar or longer period. The annex provides standards for six types of emissions from flaring at refineries and oil and gas fields.

Royal Decree No. 114/2001, known as the Law on Conservation of the Environment and Prevention of Pollution, requires “controls for optimum exploitation” of natural resources, including oil and gas. Article 19 states that “no hazardous waste or substance shall be handled, dealt with or disposed of in the Omani environment without obtaining a permit from the Ministry.” Article 27 requires exploration concessions to include language to ensure compliance with provisions of the royal decree and its implementing regulations. Exploration and production-sharing agreements include various environmental requirements.

Legislative Jurisdictions

National laws and regulations, as implemented by national entities, govern flaring and venting.

Associated Gas Ownership

According to Article 3 of the Oil and Gas Law , all hydrocarbons are the property of the state and ownership cannot be transferred before extraction. Production-sharing contracts (PSCs) grant the rights to explore, develop, and exploit oil and gas, known as exploration and production-sharing agreements. Article 43 requires that concessionaires allocate gas that is not used for operations to the local market, as determined by the MEM. If other gas sources meet domestic market needs, the MEM and the concessionaire may agree to reduce the amount of surplus gas required to be supplied to the domestic market.

Regulatory Governance and Organization

Regulatory Authority

The MEM regulates flaring and venting. It negotiates exploration and production-sharing agreements with investor companies. All agreements are based on a template, but negotiations can lead to additional clauses and modifications, including flaring and venting restrictions. The Environmental Authority regulates environmental impacts, including from oil and gas operations.

Regulatory Mandates and Responsibilities

The MEM is responsible for reviewing and approving gas conservation plans and their annual updates. The plans include the total annual volume of gas disposed of by flaring and venting. The Environmental Authority is responsible for issuing and ensuring compliance with environmental permits for flaring emissions.

Monitoring and Enforcement

Article 23 of the Oil and Gas Law states that concession holders must allow MEM officials to inspect facilities, equipment, and extracted petroleum materials and review and copy operational records. Article 3 of the Law on Conservation of the Environment and Prevention of Pollution empowers the Environmental Authority to inspect facilities subject to the law’s provisions and relevant regulations. Environmental inspectors have judicial powers. Article 9 requires an environmental permit from the Environmental Authority for any activity that could potentially cause pollution. Article 16 empowers the Environmental Authority to ask for an environmental impact assessment (EIA) before issuing a permit. In practice, EIAs are routine for oil and gas facilities and are often conducted by specialized companies approved by the Environmental Authority .

Article 6 of the Regulations for Air Pollution Control from Stationary Sources requires an environmental permit for emissions, including from flaring in oil and gas fields and refineries, before construction or operation. Article 8 empowers environmental inspectors from the Environmental Authority to conduct ad hoc site inspections to check pollution-control systems and test emission levels and composition. Article 9 requires that operators provide a plan if requested by inspectors.

Licensing/Process Approval

Flaring or Venting without Prior Approval

Since 2017, Oman has reportedly been considering developing flaring and venting guidelines consistent with widely accepted international practices. Alignment with international practice would suggest that flaring or venting without approval would be allowed during emergencies but immediately followed by reporting to the regulator of flaring or venting details.

Authorized Flaring or Venting

International practices, which Oman’s new flaring and venting guidelines are expected to follow, typically ban all routine flaring but allow exceptions for flaring during well testing (permitted within limits) and for volumes approved in the gas conservation plan.

Development Plans

Alignment with international practices would suggest that gas conservation plans have to consider all reasonable utilization options before flaring and venting and that the MEM ensures compliance with the gas conservation plan during the development and operation of assets.

Economic Evaluation

Oman’s new flaring and venting guidelines are expected to follow international practices and build on the PDO’s practice of conducting an economic evaluation of flaring and venting projects. Since 2018, the PDO has been managing all nonroutine flaring activities using the concept of measures that are as low as reasonably practical. The PDO has developed an electronic system, Flaring Waiver and As Low as Reasonably Practical Demonstration Tool, to conduct an economic and environmental evaluation of each nonroutine flaring scenario. The PDO has tested a micro-turbine to convert flared gas into electricity at Anzauz. If replicated across Block 6, about 500,000 cubic meters (m³) of gas currently flared a day could be recovered. The PDO’s Gas Directorate, through its energy management efforts, saved 46,000 m³ of natural gas a day that was previously flared or used as a fuel, in 2019.

At the end of 2018, the PDO issued a request for bids from companies with proven gas-to-power technology and experience using gas being flared. In early 2021, Japan’s Sumitomo Corporation and an independent Omani company, ARA Petroleum, initiated a feasibility study on a project to produce hydrogen from associated gas from ARA’s oil field that would otherwise be flared. In addition, a 20-megawatt solar farm will provide electricity to a methane steam reformer for hydrogen production. Oman has been trying to promote hydrogen, and several companies have expressed interest in pursuing hydrogen projects in special economic zones in Oman.

Measurement and Reporting

Measurement and Reporting Requirements

According to the Regulations for Air Pollution Control from Stationary Sources , air emissions listed in the appendix are to be measured by instruments. Fugitive emissions can be estimated using mass balance equations. Flaring and venting guidelines under development since 2017 suggest that reporting will be required to ensure compliance with targets to be established.

Measurement Frequency and Methods

In 2019, all PDO flare stacks were mapped to identify any unmetered or unreported streams. The PDO also established a dashboard to make flaring data available and more visible across the company.

Engineering Estimates

See section 13. No additional details on engineering estimates could be found in the sources consulted.

Record Keeping

No evidence regarding record-keeping requirements could be found in the sources consulted. However, the Oil and Gas Law and the Law on Conservation of the Environment and Prevention of Pollution empower the inspectors to access records to ensure compliance with laws, regulations, and permits (see section 8 of this case study).

Data Compilation and Publishing

No evidence regarding data compilation and publishing could be found in the sources consulted. However, the PDO reports flaring data from its operations in its annual Sustainability Reports. Two blocks operated by Occidental Oman use the CDM mechanism (see section 22 of this case study). CDM monitoring reports include data on recovered volumes of associated gas that would otherwise have been flared or vented.

Fines, Penalties, and Sanctions

Monetary Penalties

Chapter 8 of the Oil and Gas Law does not specify any penalties for violations of Article 39, which sets environmental requirements with respect to gas or violations of Articles 41–43, which outline provisions regarding gas use. However, Article 51 of Chapter 8 allows the minister of energy and minerals to determine penalties for violations of articles of the law not specified in the chapter.

Article 31 of the Law on Conservation of the Environment and Prevention of Pollution deals with monetary penalties for violating certain articles of the law, including the need to obtain a permit and the prohibition on emitting more than the limits in the permit. The fine is set at RO 200–RO 2,000 (about US$520–US$5,200 as of September 2021), with an increase of 10 percent a day starting four days after notification of the violation. Article 36 provides for a fine of up to RO 500 (about US$1,300 as of September 2021) if environmental inspectors are prevented from exercising their powers. Article 40 sets a fine of between RO 1,000 and RO 5,000 (about US$2,600–US$13,000 as of September 2021) in case of failure to comply with Article 27, which calls on operators to establish “controls for optimum exploitation” of natural resources, including oil and gas (see section 3 of this case study). The penalty is doubled for a repeat violation.

Nonmonetary Penalties

According to Article 31 of the Law on Conservation of the Environment and Prevention of Pollution , the suspension of activity is possible if a violator does not correct the offense within a month. According to Article 32, the use of falsified data or statements to obtain an environmental permit is punishable by up to six months in prison, a fine of up to 5 percent of the invested capital, or both. The permit may even be canceled, in which case the activity must cease. Article 36 allows for prison time of up to three months if environmental inspectors are prevented from exercising their powers. This imprisonment can be in addition to a fine. The court may also shut down the facility for up to a month.

Enabling Framework

Performance Requirements

The PDO has followed the practice of minimizing routine flaring in new installations and the principle of reducing flaring and venting to as low a level as reasonably practicable. The Regulations on Air Pollution Control from Stationary Sources set limits on six pollutants that can be emitted from flaring in petroleum fields and refineries. They also state that any combustion cannot emit smoke darker than “shade 1 on the Ringlemann Scale (20 percent opacity).”

Fiscal and Emission Reduction Incentives

Chapter 7 of the Oil and Gas Law provides several provisions with respect to natural gas. Article 41 requires the concessionaire to preserve natural gas and allows its exploitation, with MEM approval, to enhance oil recovery, store it underground, commercialize it, or use it for any other purposes as decided by the MEM. Article 42 provides for “features, incentives and facilities to encourage gas exploitation” to be stipulated in the concession agreement. For example, the concessionaire is allowed to recover gas discovery expenses if the MEM decides to postpone production to meet future domestic market demand.

Use of Market-Based Principles

Oman has two associated gas recovery and utilization projects under the CDM, both operated by Occidental of Oman and hosted by the MEM, representing the government. The first project, at Block 9, was registered in December 2012. The recovery of associated gas that would otherwise have been flared or vented started in 2010. Over the crediting period (December 31, 2013–December 30, 2020), about 2.1 billion cubic meters (bcm) of associated gas was recovered, with an average methane content of about 70 percent. The project had reduced emissions by about 4.2 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) by the end of 2020. The second project, at the Khamilah oil field area in Block 27, was registered in August 2020. Over the crediting period (August 3, 2020–August 2, 2030), about 2 bcm of associated gas is estimated to have been recovered, with an average methane content of about 78 percent. The project is expected to reduce emissions by about 0.43 million tCO2e annually.

Negotiated Agreements between the Public and the Private Sector

The Minister of Energy and Minerals is also the chairman of the board of directors of the PDO. The board also includes other representatives from the MEM as well as representatives from the Ministry of Finance. The government’s stake in the PDO is 60 percent; private companies own the remainder, with Royal Dutch Shell holding the largest share (34 percent). In essence, all projects involving the PDO are public-private partnerships, including efforts to reduce flaring (see section 12 of this case study).

The government issued the Public Private Partnership Law as Royal Decree No. 52/2019 in 2019 and its implementing regulations in 2020. The law does not specify or restrict types of projects if they improve public services and align with Oman’s economic development strategy. The law was partially motivated to relieve pressure on the government’s budget. The same rationale also induced the creation of Energy Development Oman, in late 2020. The law offers another avenue for the efforts of the PDO and other companies to reduce flaring and meet Oman’s growing gas demand. The MEM, together with operators, may pursue the aggregation of associated gas from different locations to achieve the economies of scale needed to make utilization projects financially viable.

Interplay with Midstream and Downstream Regulatory Framework

Natural gas consumption has been increasing in Oman, primarily to generate electricity and run desalination plants but also for use in downstream refining and petrochemicals facilities. Oman is a significant exporter of LNG, but it also imports pipeline gas from Qatar to balance domestic demand with export obligations. However, with increased investment in gas fields and, to a lesser extent, more aggressive policies toward capturing associated gas, Oman intends to phase out imports and expand domestic pipeline infrastructure.

Low domestic gas prices have presented a challenge to achieving the goal of supplying gas for domestic purposes from domestic sources. The MEM and the Oman Gas Company have supplied gas to industrial and power generation plants at prices set by a gas allocation committee, which includes representatives of the MEM and the Ministry of Commerce, Industry, and Investment Promotion (the Financial Affairs and Energy Resources Council before August 2020). These prices, as well as the price of electricity (which is almost exclusively generated by gas-fired power plants), have been below cost. The government of Oman raised natural gas prices to industry and power generation plants, but low oil prices after 2016, especially in 2020, stressed the government’s budget and slowed further price reforms.

The Energy Development Oman was created as a company that could raise capital at a lower cost than the government and undertake major energy transition projects . The Oman Gas Company, along with eight other state-owned companies across the oil and gas value chain, is now part of OQ, created in 2019. The newly integrated company is fully government-owned, but a partial public offering of shares is under consideration, as the government continues to focus on its budget deficit. The net effect of the changes cited in this section on domestic gas consumption, the development of new gas pipelines, and associated gas utilization will become apparent over the coming years.