The flaring and venting of gas (mostly methane) have long been known to be leading sources of emissions from the oil and gas industry. Another major source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, brought into focus only recently, is fugitive methane. This is emitted from equipment in production fields and during processing, pipeline transport, natural gas storage, and downstream utilization. Methane has larger short-term effects on the climate than carbon dioxide. Technologies to trace and quantify methane emissions, along with laws and regulations targeting their elimination, are still in their infancy. Given the overlap of the issues, several countries have introduced methane regulations that leverage the existing regulatory frameworks for flaring and venting in upstream operations. Some countries have also aligned regulations for fugitive emissions across the midstream and downstream segments.

According to the International Energy Agency, an estimated 82 million tonnes of methane were emitted from the global oil and gas value chain in 2022; these emissions accounted for about 25 percent of global anthropogenic methane emissions. Within the oil and gas industry, the United States, the Russian Federation, Turkmenistan, and Iraq are reported as being the largest emitters, accounting for more than 30 million tonnes of methane in 2022 (IEA 2023). Methane emissions due to upstream operations (primarily due to inefficient flaring and venting) were once thought to represent a small share of the volumes of natural gas recovered and processed (e.g., 0.8–1.8 percent of natural gas delivered to end users across the supply chain for the United States) (Littlefield et al. 2019). Advances in data collection and the use of new technologies such as drones and infrared imagery reveal that upstream methane emissions can be much more significant (primarily due to fugitive emissions, or leaks, from equipment). The geographic diversity of emission rates and differences in the metrics used make comparison difficult, but two recent studies of the Permian Basin in the southwestern United States indicate that emissions are higher than previously thought, albeit with a very large variance. Varon et al. (2023) estimated the share of fugitive emissions at 3–6 percent of methane produced in the Permian Basin. Chen et al. (2022) estimated these emissions at 6–13 percent of gross gas production in the New Mexico portion of the Permian Basin. To what extent investments in eliminating methane leaks and capturing escaping methane can be offset by the additional revenues from being able to monetize the gas remains unclear since there aren’t enough practical examples to prove the investment case.

According to data published by the World Bank’s Global Flaring and Methane Reduction (GFMR) Partnership, in 2022 global gas flaring released about 400 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, including uncombusted methane and black carbon (soot). The Russian Federation, Iraq, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Algeria, República Bolivariana de Venezuela, and the United States have been flaring the largest volumes of gas since 2020, typically in the order listed. These countries together produce 40 percent of the world’s oil each year but account for about 60 percent of global gas flaring (GFMR 2022).

The eradication of routine gas flaring and venting is a cost-effective way for the oil and gas industry to reduce overall emissions from its operations and also make a significant contribution to the reduction of global GHG emissions. Voluntary initiatives, often industry led, have been crucial in curbing emissions, although there are limits to what they can achieve. Many producers face financial constraints, and higher returns on investments in oil projects could reduce the incentives to explore alternative uses of associated gas. Although many abatement technologies are well known and may be “economic” on paper, capital expenditures in such projects are subject to a variety of risks, for example, changes in gas market prices and the failure of offtakers to honor their contractual obligations. Moreover, operators’ incentives may not consistently align with these investments, amid internal competition for capital among a variety of projects in which flare reduction investments are viewed as having insufficient rates of return. Where the cost (or risk) of investing in flaring reduction equipment exceeds the incremental revenue to be derived from the recovered gas, regulations are crucial in ensuring that producers undertake appropriate abatement actions. Many of the same considerations apply to reducing fugitive methane emissions. Once the sources of leaks are identified and measured, which could require relatively sizable investments, operators must invest in new equipment. Existing low- or no-leak technologies may help greenfield projects bypass the incremental cost of assessment if regulators require these technologies to be integrated in project design and development plans.

A small number of sites flaring significant volumes of gas make a major contribution to global totals. In 2022, 12 percent of sites accounted for 75 percent of the world’s total flaring volume (GGFR 2021). Although these large sites could be easier to regulate from a technical perspective than smaller flare sites dispersed around hundreds or thousands of wells, political economy considerations (such as the imperative to maximize governments’ oil revenues) often prevent meaningful abatement at large sites. Thus, progress is deterred, even though reducing routine gas flaring and putting valuable associated gas to productive use could contribute to economic development and create jobs.

Consistent high-level political leadership and commitment are crucial for designing and enforcing regulations for fugitive methane emissions and gas flaring and venting. Such regulations must be adapted to individual jurisdictions’ circumstances, including the country’s policies and goals; the role of the oil and gas sector in the economy; the specific structure of the domestic oil and gas industry; the size, number, and location of emission sources in upstream operations as well as across the oil and gas supply chain; and the quality and enforcement capabilities of regulatory institutions. Constructive interaction between the industry and regulators, and increased interaction among them and civil society are also essential to make regulations effective, ensure enforcement, and achieve policy targets and goals.

This report provides a general description of the legal and regulatory frameworks governing fugitive methane emissions, and gas flaring and venting in 31 jurisdictions. It represents an evolved update to GFMR’s 2022 review of gas flaring and venting regulations and focuses increasingly on methane emissions. This report summarizes information collected on fugitive methane emissions and gas flaring and venting, including laws, regulations, decrees, standards, and other relevant government documents, as well as information on experiences with monitoring and enforcement, if available, through September 2023. It draws lessons on the selected approaches and the effectiveness of the regulatory framework and institutional governance. A companion report provides a comprehensive legal and regulatory overview of the main oil- and gas-producing regions (GFMR 2023).

Countries were selected for the review based on the availability of information on regulations governing fugitive methane emissions, and gas flaring and venting, and whether the jurisdiction is a major oil and gas producer. The review includes an analysis of subnational jurisdictions in Canada and the United States, for a total of 31 case studies in the following regions:

• Europe: European Union (EU), Norway, the Russian Federation, and the United Kingdom

• North America: Canada (federal and the provinces of Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan), Mexico, and the United States (federal onshore and offshore and the states of Colorado, North Dakota, and Texas)

• Latin America: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and República Bolivariana de Venezuela

• Sub-Saharan Africa: Angola, Gabon, and Nigeria

• Middle East and North Africa: Algeria, the Arab Republic of Egypt, Libya, Oman, and Saudi Arabia

• Asia: Indonesia, Kazakhstan, and Malaysia

• Australia

In contrast to methane emissions, for which a reliable historical track record is not available, flare gas volumes have been tracked since 2012. The global volumes of gas flared decreased by 3 percent over 2012–22, whereas oil production increased by 5 percent. Flaring intensity (volume of gas flared per barrel of oil produced) is an indicator of how effectively a country utilizes gas. Flaring intensity grew significantly in República Bolivariana de Venezuela (275 percent), Mexico (100 percent), Argentina (83 percent), and Ecuador (69 percent), while decreasing significantly in countries such as Kazakhstan (-77 percent), Colombia (-69 percent), Brazil (-62 percent), and Norway (-59 percent).

More projects to eliminate methane leaks and abate gas flaring and venting would help countries fulfill their climate mitigation commitments. As pressure grows to decarbonize the world economy and reduce production emissions from oil and gas, such initiatives could help distinguish oil and gas with lower climate footprints in export markets and for investors, for whom the transition to a low-carbon future is becoming an increasingly important factor in capital allocation decisions. For example, as part of its climate policies, the EU is introducing monitoring and reporting requirements for all energy imports into the common market area. Meanwhile, the GFMR’s recently introduced metric, the Imported Flare Gas Index, shows how large oil importers are indirectly exposed to emissions from flaring during the production of the oil they are importing. Once reliable methane emissions data are available, this perspective could be expanded to all emissions due to oil and gas production.

To facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the current challenges and potential solutions and opportunities resulting from the approaches of the analyzed jurisdictions, this report is organized in two parts. The first part deals with the methodologies for developing effective regulations for fugitive methane emissions and gas flaring and venting; the economic evaluation of gas utilization; and stakeholder consultation. The two broad regulatory approaches considered are (1) a prescriptive approach, which focuses on specific and detailed laws and regulations with which operators must comply, and (2) a performance-based approach, which emphasizes collaborative agreement on realistic objectives and targets that operators are to demonstrate having achieved.

The second part of this report derives lessons, cites examples of what drives and hinders effective regulation on a country-by-country basis, draws conclusions, and provides recommendations.

Developing Effective Regulations for Methane Emissions and Gas Flaring and Venting

The goal of reducing anthropogenic methane emissions gained prominence following the creation of the Global Methane Pledge in 2021. Policy makers’ heightened degree of focus on methane also reflects both its potency as a greenhouse gas (GHG) and the many opportunities to reduce its emissions across the oil and gas supply chain. Methane has over 80 times more global warming potential (GWP) than the same mass of carbon dioxide (CO2) over a 20-year time frame or about 28 times more GWP over a 100-year time frame. The choice of GWP is important for the design and effectiveness of regulations or market-based solutions (such as an emissions trading system [ETS] or a GHG tax).

The oil and gas industry is estimated to emit 25 percent of all anthropogenic methane emissions, or about 5 percent of total GHG emissions. Extensive measurement of methane leaks indicates that the oil and gas industry’s share of total GHG emissions may increase.

Reducing emissions from the oil and gas industry, especially its upstream segment, is commonly seen as easier than reducing emissions from other large sources of anthropogenic methane, such as the agriculture and waste sectors. This is because technologies to detect and mitigate emissions already exist or can be developed relatively easily, given the oil and gas industry’s advanced scientific and engineering capabilities and financial means.

Countries’ experience with flaring and venting regulations can be leveraged when regulating methane emissions from upstream operations. Venting and incomplete combustion of associated gas (e.g., in flares or on-site power generation) are major sources of methane emissions. Wellhead activities such as liquid unloading and hydraulic fracturing, and standard equipment such as pneumatic pumps and controllers; compressors; and storage tanks for oil, condensate, and produced water can also be sources of considerable fugitive emissions. As already seen in some jurisdictions, the existence of technologies to lower emissions allows for prescriptive regulations such as the requirement to replace high-bleed pneumatic devices with low- or no-bleed devices, to increase the use of vapor recovery units, and to replace gas-fueled equipment with electric pumps and compressors.

Some jurisdictions have already incorporated methane emission regulations into existing regulatory frameworks for gas flaring and venting. Others pursue separate regulations for methane, generally consistent with existing regulations focused on flaring and venting. Jurisdictions where policies mandate the beneficial use of associated gas have for some time pursued bans on gas venting and mandated efficient flaring and combustion. Many of the relevant measurement and mitigation measures can also be implemented across the natural gas supply chain, including for processing plants, transmission and distribution pipeline networks, and storage facilities. However, these midstream and downstream operations are not well developed in some countries, and these operations may be regulated by an entity independent from the upstream regulator or they may be operated by a state-owned enterprise. These value chain segments also call for distinct technological and customer service considerations.

The analysis of existing legal and regulatory frameworks undertaken for this report demonstrates that the means to tackle routine flaring and venting are known and can produce results beyond what has been achieved to date. These results include the reduction of methane emissions resulting from venting and inefficient flaring. However, outdated legal and regulatory provisions, a lack of capacity to monitor and enforce existing regulations, an insufficiently integrated domestic gas value chain (and, hence, a lack of a deep gas market), and inadequate consideration of external drivers can reduce the impact of well-intentioned laws and regulations that might otherwise be effective.

Many of these factors also pose obstacles to reducing fugitive methane emissions, which typically require regulatory guidance distinct from flaring and venting regulations. However, the key challenge is the lack of reliable data on fugitive methane emissions that are detailed by source and for long enough to establish baselines and deduce trends. Without such data, regulations with reduction targets, performance requirements, penalties, and other conditions cannot be developed effectively. Regulations addressing methane emissions should therefore include fundamental requirements such as the development of methane detection technologies within predefined time frames and the resulting detection and repair campaigns. In particular, leak detection and repair requirements have been central to developing methane emission databases in jurisdictions pioneering methane regulation.

This section identifies key structural enablers and barriers and derives recommendations on developing effective laws and regulations.

Adjusting to the Specific Circumstances of the Industry

Because of its size, economic and political relevance, and broad impact on topics of national or regional importance (e.g., energy security, environmental quality, and public finance budgeting), the oil and gas industry is subject to multiple external pressures. The long life of assets requires operators to constantly update themselves with the latest technologies, and regulators to develop, update (when necessary), and enforce standards. In jurisdictions where regulation involves multiple agencies (e.g., the oil and gas regulator and the environmental regulator), verification and enforcement of laws and regulations can be challenging and costly. While large companies may be able to handle a multiplicity of regulations, smaller firms may struggle. Smaller firms may therefore oppose detailed regulations, viewing them as excessively burdensome.

In response to these challenges, regulators can prescribe broad standards that can be applied in general for all regulated activities, setting the boundary conditions for predetermined categories such as industry segment, age, type of facility, or type of technology or equipment used. This approach can be further adjusted to local circumstances by setting requirements on a case-by-case basis—through individualized permits, bidding rounds, concession terms, or contractual provisions; the requirements may be crafted for individual permits or contracts, depending on a project’s attributes. This approach may be especially appropriate in jurisdictions with a few large international oil companies, where regulators can also negotiate specific terms for individual sites. Transparency concerns and the impression of favoritism—two related issues often arising in the context of individualized permits—can be addressed through public disclosure of permits and data on fugitive methane emissions, and flaring and venting volumes, which also tend to foster stricter compliance with regulations.

Oil-producing countries whose national oil companies work with other firms often have a different regulatory regime from jurisdictions in which the industry is entirely market based, with equal treatment of all producers. Having a relatively weak agency regulate a strong national oil company creates the risk of regulatory capture. The national oil company can become a self-regulated entity or a state agent acting de jure or de facto as a coregulator of investors operating in the country. The result is a national oil company that is subject to different rules from all other producers. In some countries, national oil companies are de facto exempt from compliance. Further, the national oil company may be required to meet certain production targets that do not align with the goal of abating emissions from sources of fugitive methane, and abating gas flaring and venting, or may be required to redirect financial and human resources to projects that are outside the oil and gas industry but considered important by the government.

Efforts to regulate national oil companies have gained ground, notably in Latin America. Often, however, arm’s-length relations between regulators and national oil companies are difficult to maintain. For example, in 2016, Mexico’s hydrocarbon regulator set guidelines for the national oil company, Pemex, to reduce gas flaring and venting. However, a lack of financial resources and other investment priorities have prevented major gas abatement projects from being implemented. Ecuador convinced its national oil company, Petroecuador, to work toward eliminating routine gas flaring by establishing an initiative promoting increased use of associated gas to generate electricity and produce liquefied petroleum gas.

Prerequisites apply if laws and regulations governing fugitive methane emissions, and gas flaring and venting, are to be effective, implementable, and enforceable. Early engagement with all stakeholders—regulatory agencies, national oil companies (where they are important players), producers, other industry players (e.g., contractors, technology providers, and financial sponsors), affected communities, and other segments of civil society—can facilitate a greater understanding of the laws and regulations and create opportunities to seek assurance and adjust regulations.

Some regulators have committees that represent different stakeholders and craft or recommend regulatory language through a collaborative process. In Canada, for example, the Saskatchewan Petroleum Industry–Government Environment Committee was formed to facilitate the cooperative resolution of provincial environmental management issues, including climate change and gas flaring and venting. Brazil’s National Policy Energy Council, which is responsible for formulating energy sector policies, comprises government representatives, energy experts, and nongovernmental organizations.

In Alberta, Canada, operators must consult annually with, and address the concerns of, residents within a prescribed distance from a gas flare. For communities not well versed in the safety risks posed by nearby flaring and venting, the outreach strategy may also include an educational component.

Recommendations

- When formulating new regulations, governments should consider their own established good practices as well as experiences from other jurisdictions that are most applicable to their situations. Abatement measures can be enhanced and implemented more rapidly if oil- and gas-producing countries share advice among themselves.

- Consulting key public and private stakeholders, including the oil and gas industry, on the development of regulations is an essential starting point for a functioning legal and regulatory framework.

- In formulating regulations, leveraging the oil and gas industry’s technical and financial capabilities, and voluntary actions to reduce emissions (say, due to environmental, social, and governance, or gas buyer standards) can kick-start reduction efforts.

- Boundaries should be established between the regulator and the national oil company to avoid conflicts of interest.

- The responsibilities of separate regulators must be clearly identified, and duplicative and conflicting requirements must be avoided.

Determining Reliable Volume Baselines for Methane Emissions by Widely Deploying Existing and New Measurement Technologies and Approaches

Governments committing to methane emission reduction targets and initiatives like the Global Methane Pledge make a commitment to establish a robust methane emission inventory. Building this inventory requires monitoring and reporting of methane emissions across all sectors, using state-of-the-art technologies.

To track progress against methane targets and monitor the effectiveness of methane regulations across the oil and gas industry, governments need:

• An agreed emission figure for the baseline year, against which progress will be tracked, and

• Mechanisms to quantify the emission reduction achieved with interventions within the sector as regulations and reduction activities are implemented.

Baseline emissions are needed by source (and ideally for all sources) and must be adjusted for background emissions. For example, the Northern Territory (Australia) requires a regional methane assessment to characterize existing natural and anthropogenic sources of methane emissions in a license area and in adjacent areas before exploration commences and immediately after full-scale production begins. The Northern Territory also requires baseline methane assessments and routine periodic atmospheric monitoring of methane emissions.

Oil- and gas-producing countries with effective regulations, such as Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Norway, have a history of success monitoring, reporting, and verifying asset- and basin-level greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This history provides at least some data against which the performance of baseline as well as future emissions can be established. However, despite legacy regulations like the United States’ Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, recent scientific studies utilizing methane detection and measurement technologies (e.g., Zavala-Araiza et al. 2018; Alvarez et al. 2018; Zhou et al. 2021) have shown that legacy methodologies typically underestimate methane emissions from oil and gas facilities. This is primarily because such methodologies rely heavily on emission-factor-based estimates rather than direct measurement of methane emissions. In each of these studies, methane emissions, when measured directly, have been shown to exceed reported estimates and show a “‘fat tail” distribution, with a minority of super-emitting sources responsible for the majority of emissions. In the studies conducted in the United States in particular, almost all these super emitters were unplanned, previously unknown, and their prominence resulted from malfunctioning or leaking equipment. Regularly surveying facilities using methane emission measurement technology makes robust leak detection and repair (LDAR) possible. However, it is problematic to quantify the reductions achieved especially when baseline year estimates may not have initially accounted for unknown super emitters.

The studies referenced in the previous paragraph are predominantly based on ground-level measurements across various regions. Varon et al (2023) and Chen et al (2022), referenced in the Introduction section, are based on satellite data on operations in the southwestern United States’ Permian Basin. There are also differences in geography and measurement/estimation methods. Nevertheless, all of the referenced studies indicate greater emissions than previously assumed. Overall, these studies underline a need for more accurate and more frequent, if not continuous, assessment of methane emissions to establish baseline and background emissions and historical trends, upon which effective industry and regulatory practices can be built. Existing technologies offer immediate solutions to address some emission sources, but innovation is needed to identify technologies that are most appropriate and cost-effective for different geographies, operations, and equipment. While private and public actors are developing technological solutions to cost-effectively produce reliable data, no industry standard has yet emerged. To encourage innovation, performance requirements (e.g., emission intensity) can stimulate innovative practices and may be adjusted as more data are gathered and analyzed.

Countries with little to no history of GHG monitoring and reporting and little to no application of direct methane measurement technologies find it even more challenging to establish baseline emissions and monitor emissions from oil and gas operations.

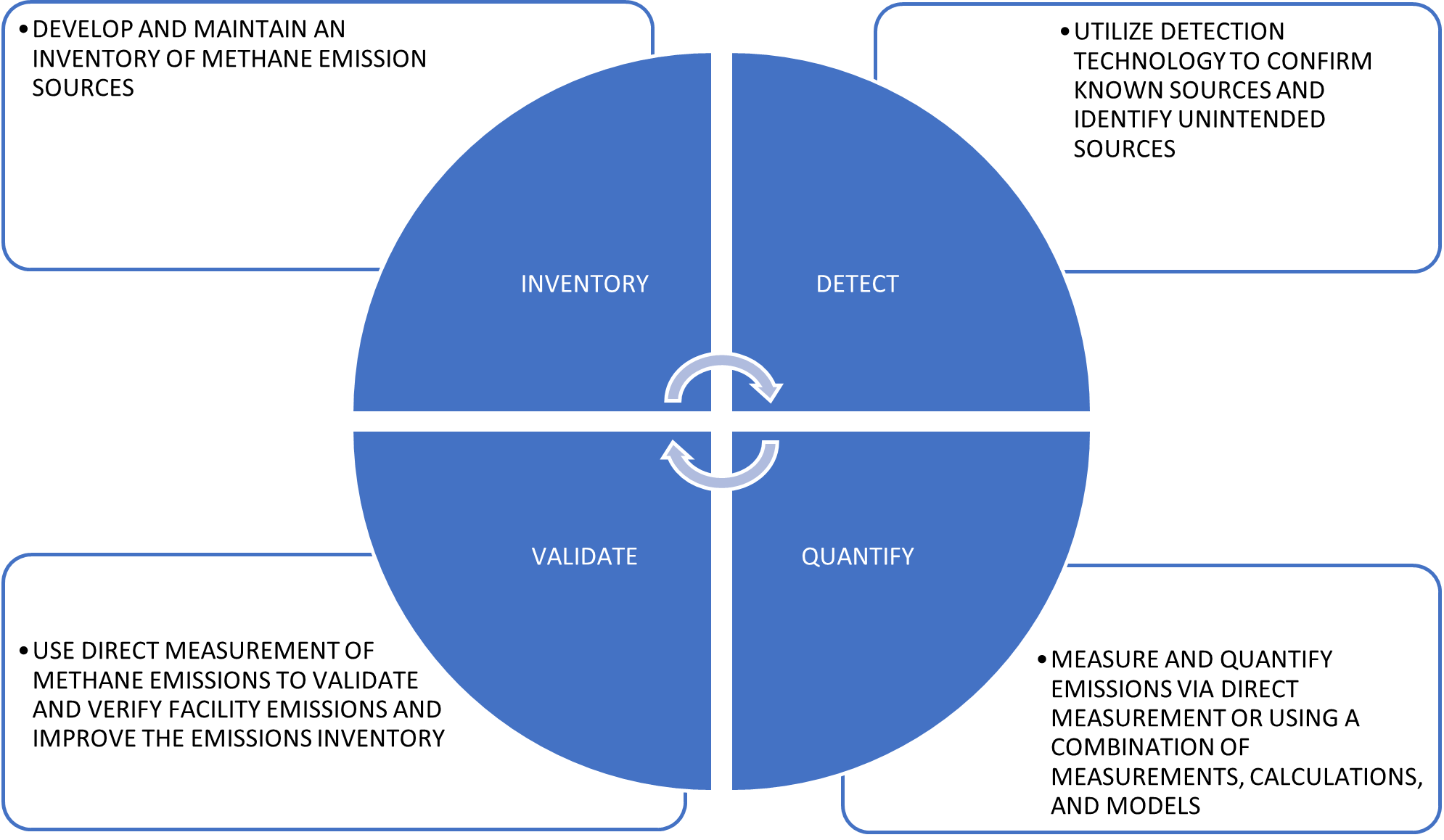

Figure 1.1 outlines the key elements of a robust methane monitoring, reporting, and verification program for a typical oil and gas facility. The first step is for the facility’s operator to establish an inventory of methane emission sources for each area of the facility. Initially, generic global emission factors may be used to estimate emissions from these sources. However, as the program develops, these estimates should be reconciled with data gathered during routine LDAR surveys using technologies to measure and quantify actual methane emissions directly or indirectly. Direct measurement of methane emissions also presents an opportunity to monitor and validate the facility’s methane emission rate.

Figure 1.1 Key Elements of a Technical Methane Program

These building blocks are broadly the same when a national oil and gas emission inventory is considered. Governments can develop regulations mandating regular LDAR surveys, complemented with regulations mandating operators’ participation in a methane emission monitoring, reporting, and verification program. Both operators and governments (and others) can then leverage methane measurement technologies to monitor and validate reported emissions and support LDAR efforts.

Recommendations

- A reliable baseline for methane emissions must be defined as a prerequisite for assessing progress and incentivizing action, for example, through prescriptive or performance-based regulations.

- Regulations should therefore require or encourage private sector participants to implement existing technologies to mitigate known emissions; develop the necessary technologies to measure and inventory their emissions from all sources; and implement

- LDAR programs. These goals can be achieved by implementing the necessary incentives such as monetary sanctions for noncompliance or poor compliance.

- As technology advances and reliable long-term datasets emerge, regulations will have to evolve to achieve maximum emission reduction.

Table 1.1 outlines some of the key available technologies for quantifying and validating methane emissions.

Table 1.1 Key Methane Measurement Technologies

|

Technology type |

Capability |

Benefits |

Challenges |

|

Satellites |

Detection thresholds: 10,000 kilograms (kg)/hour to 100 kg/hour

Regional/global coverage with monthly to daily revisit times depending on the satellite |

Noninvasive, potential to be lowest cost

Useful in identifying super-emitters |

The constraints of orbital routes may prove to be a barrier to regular site-level monitoring

High detection thresholds restrict detection to very-high-emission sources only

Cannot detect over water (offshore) or on cloudy days

|

|

Aircraft |

Detection thresholds: 50 kg/hour to >3 kg/hour

|

Capable of surveying a number of facilities in a single flight depending on facility density

Best-in-class providers will capture most facility emissions |

Technology providers tend to be limited to North America

Permissions required for facility overflights |

|

Drone/ unmanned aerial vehicles |

Low detection thresholds, >1 kg/hour, are possible with favorable weather conditions and site access |

Capable of surveying a number of facilities in a single day depending on facility density

Able to scan entire facilities, including areas that are difficult to reach using other methods/approaches, and may be able to pinpoint exact sources of emissions |

Sensitivities surrounding drone deployment in some jurisdictions

May require qualified drone pilots to be available

Access restrictions and stacked facility design may limit use for offshore facilities |

|

Vehicle-mounted/mobile |

Low detection thresholds, >1 kg/hour, are possible with favorable weather conditions |

Can survey around facilities’ fence line, avoiding issues with site access

Capable of surveying a number of facilities in a single day depending on facility density

|

Limited to onshore operations only

May overlook emissions at an elevation if a plume is not sampled/encountered during the survey |

|

Fixed-point sensors |

Detection limits vary with number of sensors and sensor placement |

Can be configured to provide facility-scale, near-continuous monitoring

Can provide early alert of emissions to enable rapid response |

Can detect emissions blown in from nearby facilities

|

|

Handheld, manual devices |

Low detection limits, typically >1 kg/hour |

Able to pinpoint exact sources of emissions

|

Does not quantify emissions without additional leak rate sampling

Resource intensive

May be difficult to survey sources at an elevation

|

Adopting a Multilayered Approach to Designing and Implementing Regulations

A significant share of upstream methane emissions stem from gas venting and inefficient or incomplete flaring and other combustion of gas (e.g., on-site electricity generation). Regulations prohibiting venting and imposing strict performance criteria on flaring and other combustion can reduce methane emissions significantly. Adopting mandates that ensure market access for associated gas before production would further reduce flaring and, thus, methane emissions. The captured gas’s net commercial value can be considered in the design of regulations if market access is already available or can be facilitated relatively cheaply. Using gas at the production site or in nearby industry facilities is another way to reduce emissions.

A regulatory approach that will ensure these potential emission reductions requires as key design inputs data on gas production, gas composition, and emissions from leaks, flaring, or venting. To reduce emissions cost-effectively and as quickly as possible, operators as well as regulators require adequate baseline data and reliable procedures for tracking progress. A fit-for-purpose measurement method must be identified to monitor performance and enforce procedures to ensure compliance. Countries lacking strong regulatory agencies may need to make substantial efforts to estimate emissions and monitor compliance; the additional inspection protocols and reporting requirements to ensure compliance could otherwise become a financial and administrative burden.

While many jurisdictions have flaring and venting regulations, some very detailed and specific, volume measurement and reporting may not be sufficiently rigorous, or consistent, to achieve the greatest possible emission reductions. Additional regulations are often needed to control fugitive emissions associated with pneumatic devices, storage tanks, and other equipment. Although measurement and leak detection technologies have been available for some time, they were not used consistently, even in jurisdictions with stringent environmental oversight such as Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

Fugitive methane emissions occur across the upstream, midstream, and downstream segments of the oil and gas industry. Thus, a regulatory approach that pursues frequent, if not continuous, monitoring of all fugitive emission sources across the complete oil and gas supply chain, could encourage the deployment of fit-for-purpose technologies for facilities across locations.

A commonly used regulatory approach for measurement, reporting, and verification is based on command and control. It introduces standards related to attributes such as gas volume, gas composition, the height of flare discharge, and similar operational characteristics. Many jurisdictions are increasingly introducing LDAR standards to identify and quantify leaks, that is, sources of fugitive methane emissions. These standards are often associated with regulations or contractual obligations, as well as the measures deployed by regulators for monitoring compliance. The standards may specify the technologies to be used for different equipment and operations, the frequency of leak detection, the sources to be monitored, and repair technologies and timing.

It is far more challenging to promote the commercialization of otherwise flared or vented gas or gas captured from fugitive sources; this depends on several factors often outside an upstream regulator’s control. For example, the regulations administered by separate regulators often influence the availability of transport infrastructure or the ability to build new pipelines. Regulations setting prices and rates may influence downstream customers’ ability and willingness to accept associated gas. Self-use at production sites or nearby upstream facilities may avoid these midstream and downstream difficulties but may face technical and economic obstacles.

Successful regulatory approaches are therefore often complex. A targeted approach has proven to be effective for combining standards that place limits on fields, equipment, units, or other combinations, without rigidly prescribing a method or restricting the means of achieving the desired results. This allows operators to prioritize investments as they see fit. This regulatory approach employs specific performance metrics (e.g., minimum gas utilization rates or limits on the gas flared or vented as a percentage of the total gas production, or methane intensity) or establishes performance requirements (e.g., process or equipment standards, such as requiring 98 percent flare gas combustion efficiency or 95 percent reduction in fugitive emissions). These metrics and requirements can be applied at the level of a company, facility, or piece of equipment.

Many jurisdictions with regulatory capabilities and significant industry presence and experience pursue such a targeted approach. Often, individual permits are required for each facility or exploration and production area. Gas utilization or methane management plans are also required in some jurisdictions. For example, in Mexico, before exploration, an operator indicates the volumes of associated gas that can be utilized under the given circumstances. The regulator then reviews the associated gas utilization program to establish targets. For production, Mexico has established an annual associated gas utilization rate of 98 percent, which must be reached within three years of the start of operations. Consistent with these utilization requirements, Mexico’s methane emission guidelines require prioritizing gas capture technologies over gas flaring to reduce emissions from tanks and other equipment. The regulator and the operator are expected to work together to find the best solution for a particular field.

To allow for a smooth transition from existing flaring and venting regulations toward a more flexible yet comprehensive approach that emphasizes all methane emissions, some countries are introducing new regulations in phases, setting different compliance deadlines for new and existing facilities. The United Kingdom, for example, requires that all new developments be designed for zero routine flaring and venting, whereas existing facilities have until 2030 to comply. The North Sea Transition Deal, a public-private partnership, commits the offshore oil and gas industry to a 50 percent reduction in methane emissions by 2030 relative to a 2018 baseline. This should be consistent with a methane intensity commitment of 0.25 percent by 2025, with an ambition to reduce it to 0.20 percent.

Phased implementation allows regulators to increase requirements and targets incrementally over time, allowing producers more time to adapt. This approach promises to be particularly useful for regulating fugitive methane emissions given the lack of sufficiently detailed historical data by emission source. Starting with reduction targets that are reasonable based on available data, requiring LDAR and measurements to enrich the methane emission database, and adapting targets according to new information appear reasonable phases for developing enforceable regulations. Steady improvement and mainstreaming of innovative detection methods (e.g., continuous monitoring systems, aerial surveillance, and satellite instruments) facilitate monitoring and enforcement (see table 1.1 for some of the technology choices regulators can use to verify reported emissions and enforce compliance with the limits set in regulations or licenses).

Recommendations

- Fit-for-purpose measurement methods (both metering and engineering estimates), reporting, and monitoring are essential to define regulatory priorities, starting with areas where abatement actions are likely to have the most impact.

- Priorities can be addressed in phases by gradually introducing new laws and regulations. This phased approach fits the needs of regulating fugitive methane emissions amid the growth of measurement and reporting requirements and technologies, which should lead to more data and better information.

- To optimize the functionality of the laws and regulations introduced, countries can adopt a targeted approach that helps them balance prescriptive rules detailing what is required to reduce flared and vented volumes, as well as fugitive methane emissions, and performance-based standards that aim to reduce emissions across facilities, without rigidly prescribing a method to achieve the desired results.

- In the meantime, technologies known to lower fugitive emissions (e.g., low- or no-bleed pneumatic devices) should be promoted over higher-emission versions, especially in new projects awaiting a permit.

Assessing the Economics of Associated Gas Use

The use of associated gas continues to face significant economic barriers. In most countries, before being allowed to flare or vent associated gas, operators must demonstrate that the projects recovering gas cannot meet the hurdle rate of return (the threshold net present value or internal rate of return). In some jurisdictions, field development plans are not approved until operators conduct an economic evaluation of all reasonable gas utilization alternatives, including self-use, reinjection, or gathering and treatment for sale in downstream markets. Operators are allowed to flare only once they can prove that the incremental benefits of using associated gas are lower than the incremental costs. Many jurisdictions prohibit venting (except for narrowly defined emergency and safety conditions) to reduce methane emissions. As better measurement enables gathering more data on fugitive emissions from pneumatic devices, storage tanks, gathering systems, and other upstream facilities and equipment, utilization requirements also apply for gas to be captured from leaks. Alberta requires each operator to perform an economic evaluation for all available associated gas utilization alternatives and utilize the gas whenever it is economic to do so. Gas may be flared or, if unavoidable, vented only if none of the alternatives meet the required hurdle rate, specified as a net present value of less than Can$55,000 (about US$44,000 as of August 2021). The economic analysis may be repeated on a before-royalty basis to take advantage of a royalty waiver program. A decision tree approach based on three principles is required for the economic analysis:

- Flaring and venting are first evaluated for elimination.

- If emissions cannot be eliminated, flaring and venting are evaluated for reduction.

- If emissions cannot be reduced, the flaring and venting source must meet specified performance standards.

Also, since 2018, fugitive emissions have been managed based on a systematic program of LDAR and the identification of and repair of malfunctioning equipment. The regulator in Alberta requires operators to develop and document a Methane Reduction Retrofit Compliance Plan, which includes a schedule to replace and retrofit existing equipment and allocates funds to reduce venting. The plan must set an overall limit on the volume of vented gas at all existing and future oil and gas sites by 2023.

Other jurisdictions have similar requirements of economic assessment for gas utilization or conservation projects. This incremental approach has several challenges depending on the jurisdiction. The financial return on projects to reduce flaring, venting, and fugitive emissions depends critically on the price received for the gas captured and taken to market. If the price is too low—due to oversupply or market or regulatory distortions, for example—the financial return on investments will be too low or even negative (UNECE 2019), substantially reducing or even removing the incentive to capture associated gas. Equally limiting is poor payment discipline in the domestic market, whereby gas purchasers do not pay for gas fully or on time. This is a problem even when prices on paper appear sufficiently high; it is worse when the government keeps domestic gas prices artificially low. In either situation, because there is little or no incentive to sell gas in the domestic market, governments often impose a domestic supply obligation on gas producers—a response that is neither effective nor sustainable.

Alternatively, the economics of associated gas use may be determined as part of the overall project approval process—considering the negative externalities of fugitive methane emissions and flaring and venting, the cost of which must be considered when assessing the viability of oil field development. Possible ways to integrate these externalities in the economic evaluation include pricing GHG or charging royalties or fees on gas lost due to leaks, flaring, and venting.

Regulators in several countries and jurisdictions have been implementing this integrated approach or several of its elements (e.g., development plans mandating zero flaring or venting, minimal methane emissions, royalties on lost gas, emission taxes). These include Brazil, Alberta, British Columbia, Colombia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States (especially in the proposed regulations of the US Environmental Protection Agency and the Bureau of Land Management, and certain clauses in the Inflation Reduction Act). For example, for greenfield oil and gas projects’ field development plans to get the UK Oil and Gas Authority’s approval, the projects must include zero routine flaring and venting and gas recovery systems, besides low-carbon electricity alternatives, precision GHG measurements, and new technologies to reduce emissions. To lower investment barriers, regulators can price environmental externalities to incentivize the use of captured gas or establish financial incentives for expenditures on abatement technologies. The market value of captured gas (methane) can be another input in these calculations.

The integrated approach is likely to generate more reductions in fugitive emissions, flaring, and venting than the incremental approach. Meanwhile, the incremental approach could lead to effective results under certain preconditions. For example, some jurisdictions require producers to commit to gas evacuation infrastructure before project development, request an evaluation of opportunities for joint gas utilization projects with neighboring operators, or require gas to be handed over free of charge at the license boundary (which likely requires new investment because associated gas has to be separated, gathered, and transported to the license boundary). Traditional as well as more recent technologies (e.g., enhanced oil recovery and floating, or small-scale liquefied natural gas [LNG] facilities, and electrification of previously gas-fueled equipment) offer opportunities to reduce flaring and venting as well as fugitive emissions once sources are identified and measured, at a competitive incremental cost. In contrast to the upstream segment, fugitive methane emissions across the rest of the oil and gas supply chain result from existing infrastructure (e.g., processing facilities, long-distance pipelines and their compressors, natural gas storage facilities, distribution networks); this usually means a market for the captured methane exists already. An economic assessment of fugitive emission reduction projects is incremental and covers the detection and measurement of emissions from potential sources and leak repair, often starting with the highest-emission sources. There are different technologies and operational solutions for different sources at different locations. Regulators responsible for setting pipeline tariffs and the delivered cost of gas to various end users may have to be consulted when evaluating emission reduction projects; this is to ensure costs can be reflected in tariffs and the prices for end users.

Recommendations

- For assessing the economics of associated gas use, the integrated approach has proven effective since it assumes that the associated gas use is part of the overall development rather than a separate project. The cost of abating fugitive emissions, flaring, and venting is evaluated as part of the overall exploration and production project.

- Consistent application of an integrated approach across the oil and gas industry is key to allowing comparability across projects and approaches.

- Coordination among upstream, midstream, and downstream regulators (if they are separate), and other regulators (e.g., environmental, safety, and energy) is desirable to align economic incentives or penalties and avoid duplicative or conflicting regulations.

Addressing Barriers Outside the Upstream Petroleum Sector

In many jurisdictions, the absence of a deep natural gas market has been a key challenge to mitigating upstream flaring and venting and, to a lesser extent, upstream fugitive methane emissions. Even when there is a market, several reasons have hindered access to midstream pipelines or influenced the ability to build new infrastructure (pipelines, storage facilities, processing plants, LNG export facilities). All these reasons are outside the upstream regulator’s authority. For example, regulatory approval for midstream infrastructure is administered by a separate regulator and may be challenged by a variety of intervenors, including local communities hosting infrastructure and nongovernmental organizations. Administered prices for natural gas may be set too low by yet another regulator or directly by the government, and undermine the economic viability of emission reduction and gas utilization projects.

Imprecise institutional arrangements and legal uncertainty surrounding the definition of authorities at different levels of government (national and subnational) and across agencies (e.g., hydrocarbons, energy, and environment) can result in conflicting mandates and overlaps. Varying levels of subject matter expertise and resource insufficiency in individual agencies—making it difficult to effectively meet their defined responsibilities—can further cause misalignment.

Elimination of such barriers requires the legal and regulatory framework to cover the entire value chain (production, transportation, and consumption). Governments must support an integrated energy sector strategy; ensure access to markets for associated gas; establish rules for nondiscriminatory third-party access to existing transport, natural gas storage, and gas processing infrastructure; facilitate the development of infrastructure needed to access domestic and export markets; prevent a single firm from controlling natural gas markets across the value chain; and ensure market-based pricing or payment discipline among gas purchasers.

The Master Gas System (MGS) in Saudi Arabia is among the more distinctive cases of gas use. Since the 1970s, the government, along with the world’s largest national oil company, Saudi Aramco, has financed the development of the necessary midstream and downstream infrastructure to capture and use associated gas. The MGS, primarily driven by the objective of creating economic value, led to significant reductions in flaring, venting, and methane emissions.

Kazakhstan has been promoting increased gas capture and use economywide since the 2000s. A 2012 law increased the state’s rights to acquire associated gas from producers. The national oil company of Kazakhstan partners with many international oil companies in upstream projects, and a national pipeline company builds and operates midstream infrastructure, besides procuring gas from producers at an administered price and delivering it to industries, power plants, and city networks. The price paid to producers has not always been sufficient to cover the costs of gathering, processing, and delivering to an injection point, especially for sour gas.

Other countries tried similar approaches (e.g., Nigeria’s Gas Master Plan), but their implementation was prevented by some of the barriers discussed in the beginning of this section. In North America, Western Europe, and parts of Australia, which have deep, liquid natural gas markets and experienced regulators but do not have dominant national companies or administered pricing of natural gas, such centrally directed policies cannot overcome the barriers to developing the natural gas value chain. Instead, they must be mitigated with regulatory approaches that facilitate permitting of critical infrastructure and efficient functioning of the market.

Recently, climate change considerations and the growing recognition of the need for global supply chain decarbonization have led North American and European environmental authorities to take a bigger role in methane emission abatement. Regulations and voluntary commitments to control methane emissions have added another layer of complexity to the legal and regulatory framework governing gas flaring and venting and resulted in frequent updates to existing regulations. At the same time, an integrated regulatory framework for fugitive methane, flaring, and venting may be more internally consistent and facilitate a holistic approach to reducing GHG emissions from upstream oil and gas operations cost-effectively and relatively quickly.

Alongside new legislation further restricting flaring, venting, and fugitive methane emissions, many international oil companies have announced net-zero plans and outlined new strategies to reduce their operations’ methane intensity. Besides minimizing flaring and venting, some companies (almost all of them in North America) seek certifications for responsibly sourced gas (RSG) by reducing emissions. European LNG importers and EU methane regulations impose methane footprint assessment for imports; this compels certification to include assessments of fugitive methane emissions. More LNG exporters may pursue such certifications if more importers ask for RSG-certified LNG shipments. Regulators are also following such voluntary certification efforts to incorporate operational best practices and effective measurement and mitigation technologies into their regulations. Financial institutions follow certified companies to direct their funding to the lowest-emitting companies. As a result, more oil and gas producers are expected to deploy initiatives to monitor and mitigate fugitive methane emissions as well as routine gas flaring and venting, set their own internal targets, and expand emissions reporting in their sustainability reports.

A number of national oil companies lag behind this global trend and may struggle with the capital expenditure and investment required to meet these challenges. Although some of them have reduced routine gas flaring from upstream operations, few have developed net-zero emission plans. Exceptions include Ecopetrol’s target of reducing emissions from operations by 20 percent by 2030, YPF’s target of a 10 percent reduction in carbon dioxide emissions by 2023, Sonatrach’s target of less than 1 percent of total associated gas to be flared by 2030, Petronas’s target of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, Pemex’s target of 98 percent methane use (no date), and Saudi Aramco’s zero routine flaring program and near-zero methane emissions by 2030. Several national oil companies could reduce emissions. For example, Petrobras reports no routine flaring and 97 percent average gas use. Ecopetrol had a program to reduce flaring by 8 million tons of carbon dioxide (tCO2) by 2021 and carried out some projects to reduce methane leaks from its equipment. As the primary fossil fuel suppliers and economic pillars in their home countries, national oil companies are being increasingly asked to play a critical role in the decarbonization of their domestic economies.

Recommendations

- A holistic energy and environment strategy that covers the entire supply chain can provide clarity of direction and reduce uncertainty and, as such, help regulators and the industry develop least-cost yet effective and relatively quick solutions to reduce emissions and create economic value.

- Targets must be aligned through legal and regulatory requirements and standards, and interagency coordination. This can be achieved through dedicated liaison officers.

Lessons from the Case Studies

The first part of this report highlighted some of the key structural elements and contextual circumstances that either enable laws and regulations to realize their full potential for emission mitigation or prevent it. It also highlighted the commonalities between regulating flaring and methane emissions, but also the differences, which will have to be addressed with new methods and approaches before best practices can emerge. Regulating fugitive methane emissions at scale is a relatively new policy and yet to be fully adopted across the domain of oil and gas. The industry lacks standards for measurement in terms of the technologies applied or regulatory requirements. Building on these findings and leveraging the practical insights derived from the country case studies, this chapter distills lessons on what drives or hinders effective regulation to eliminate routine methane emissions, flaring, and venting.

The chapter has seven sections, which follow the structure of the case studies included in the companion volume (GGFR 2022):

- Policy and targets

- Legal, regulatory framework, and contractual rights

- Regulatory governance and organization

- Licensing/process approval

- Measurement and reporting

- Fines, penalties, and sanctions

- Enabling framework.

Policy and Targets

Eighteen of the 23 countries covered in this report made the Global Methane Pledge, which was announced at the November 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) and whose participants aim to achieve a 30 percent reduction in cross-sector anthropogenic methane emissions. At the time of writing, 150 countries had made the pledge. Although the 30 percent target applies globally, many countries pursue 30 percent or greater emission reductions, especially in the oil and gas industry, which is estimated to be responsible for about 25 percent of the world’s overall anthropogenic methane emissions and offers scope for mitigation with existing technologies. One of the main goals of the pledge is “to continuously improve the accuracy, transparency, consistency, comparability, and completeness of national greenhouse gas inventory reporting under the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement, and to provide greater transparency in key sectors.” Such an emission inventory is especially important for developing effective regulations to reduce fugitive methane emissions.

Meanwhile, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) typically set national greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction targets that apply economywide. While these targets may cover all GHGs, including methane, NDCs are mostly silent on how methane emissions are translated into carbon-equivalent global warming potential (GWP). To consider methane’s GWP is important, regardless of whether a jurisdiction pursues a tax on GHG emissions or designs an emissions trading system (ETS).

NDCs do not yet mention fugitive methane emission reduction in the oil and gas industry except in a handful of countries, including Canada (provincial initiatives), Colombia, Mexico, Nigeria, Norway, Saudi Arabia, and the United States. For example, Nigeria’s NDC foresees a 60 percent reduction in fugitive methane emissions by 2031 as a conditional contribution (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2021). Many NDCs are not explicit about flaring and venting either. Less than half of the oil-producing countries covered in this review include gas flaring and venting reduction targets in their NDCs. Algeria, Angola, Gabon, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and República Bolivariana de Venezuela have set quantified targets. Ecuador, Egypt, Mexico, and Oman have included the topic but not specific targets. Not all countries that set flaring and venting reduction targets have adopted detailed and all-encompassing regulations to improve operational practices across the industry to meet those goals.

Meanwhile, some countries are setting targets for flaring and venting, and increasingly fugitive methane reductions. These targets cannot always be found in their latest NDCs, some of which predate their joining of the Global Methane Pledge. Abatement targets are set to avoid resource wastage; reduce local air pollution and GHG emissions; and yield various co-benefits, such as supporting the development of a midstream gas sector, expanding electricity access, and enhancing the added value of extracted oil and gas resources.

In 2016, Canada, Mexico, and the United States jointly called for a 40–45 percent reduction in methane emissions from their respective oil and gas industries by 2025. Alberta limited routine methane venting to 3,000 cubic meters (m3) per month, and total venting (including nonroutine) to 15,000 m3. British Columbia has regulations to reduce methane emissions by 10.9 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) over a 10-year period starting in 2020. Saskatchewan’s goal is to reduce methane emissions by 4.5 million tCO2e per year over 2020–25. The United Kingdom has committed to a 0.25 percent industry methane intensity by 2025, with an ambition to reduce it to 0.20 percent.

Most countries are yet to come forward with work plans to achieve the goal of the Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 initiative, and few have adopted legislation to make greenfield projects free of routine flaring and venting. But there are exceptions. In Malaysia, under the authority of the national oil company, Petronas, all new oil and gas developments must be designed for zero continuous flaring and venting. In the United Kingdom, the regulator issued guidance in June 2021 requiring all new oil and gas developments to incorporate zero routine flaring and venting; the industry has until 2030 to comply. Nigeria has set zero flaring by 2030 as a conditional contribution in its NDC. As per 2023 regulations on upstream gas flaring and venting, and methane emissions, the Nigerian upstream regulator will set biannual limits on flaring. Saudi Arabia’s NDC has a zero routine flaring target, which is also the policy of Saudi Aramco, the national oil company.

Other NDCs fall short of zero routine flaring but include reduction targets. Algeria’s 2015 NDC adopted an unconditional target of less than 1 percent of total associated gas to be flared by 2030. In Brazil, monthly flared volumes cannot exceed 15 percent of the gas-to-oil ratio defined in the approved production plan. In Argentina, wells and production facilities exceeding a specified gas-to-oil ratio are prohibited from flaring and venting, although some exceptions have been granted. The Alberta Energy Regulator limits the total annual volume of gas flared or vented at all upstream facilities in the province. If those limits are exceeded in any year, the regulator can impose reduction limits for individual sites. Mexico’s regulations specify the methodologies and criteria that operators should use for structuring their proposals for associated gas use programs and targets.

Some targets adopted in NDCs focus on gas capture and utilization. In the United States, the North Dakota Industrial Commission has, since November 2020, required companies to capture 91 percent of the associated gas they produce. In Mexico, Pemex has a target of 98 percent methane utilization, which is mentioned in its NDC.

Recommendations

- Any environmental commitment should be accompanied by a clear and implementable national roadmap for action.

- Economywide targets may be sufficient if there is an economywide carbon price or equivalent emission trading or offset systems that include an appropriate GWP for methane. In their absence, a bottom-up approach to setting sector-specific targets should be pursued.

- Governments are advised to leverage accurate data collection and reporting requirements to develop specific targets for and regulations governing fugitive methane emissions, and gas flaring and venting, alongside leveraging the industry’s expertise and capabilities. These actions will help achieve local environmental objectives and fulfill global environmental commitments.

Legal, Regulatory, Fiscal, and Contractual Frameworks

Regulations governing gas flaring and venting, and fugitive methane emissions, are anchored in legislation governing a jurisdiction’s oil and gas sector and environmental management. Primary sector legislation usually addresses such issues as jurisdiction over oil and gas, resource ownership, permit allocation, contractual rights and obligations, the right to commercialize associated gas, fiscal regimes, sector institutional organizations, and the role and functions of regulator(s). Many jurisdictions have laws that prescribe natural resource management functions and environmental policies, but do not explicitly refer to gas flaring and venting.

In our sample of case studies, only Egypt, Libya, Oman, and República Bolivariana de Venezuela did not have explicit regulations for flaring, venting, or methane emissions. Some regulations (e.g., those of Canada and its provinces, the United Kingdom, and the United States and its states except Texas) address flaring and venting in detail, mentioning what is allowed, what needs to be measured and reported (and how), and what the performance standards are. In mostly the same jurisdictions, existing and proposed methane emission regulations are integral to flaring and venting regulations, especially from upstream operations, and are detailed.

At the national level, Australia regulates GHG emissions without prescriptive limits on flaring, venting, and methane emissions, although some states and territories have more detailed regulations (e.g., the Northern Territory). Most other flaring and venting regulations are less prescriptive in one aspect or another; among these jurisdictions, only Colombia, Mexico, and Nigeria incorporate methane in their regulations. In Malaysia and Saudi Arabia, national oil companies manage flaring, venting, and methane emissions; they develop their own guidelines and procedures to achieve internal flaring and methane intensity goals. However, guidelines frequently follow established industry technical standards as defined by professional engineering societies or the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In Malaysia, these guidelines also apply to companies other than the national oil company.

The legal and regulatory framework governing gas flaring and venting, and fugitive methane emissions depends on what part of the government has jurisdiction over oil and gas resources. In unitary states, this is usually the prerogative of the national government. In federal states, two types of situations can occur. Where the federal government owns the resources in the ground, regulations are often prescribed at the federal level. Where subnational governments own the resources located within their borders, they typically regulate the industry. In practice, the two modalities may coexist, as they do in Argentina, Canada, and the United States, where different segments are regulated by national or subnational levels of government.

In countries where subnational authorities own resources, the federal government often exercises other powers, for example, regulating offshore production and coordinating and harmonizing certain roles among subnational agencies. In most cases, the federal government retains authority over environmental legislation, which primarily focuses on air quality and abatement of emissions. For example, in the United States, states are responsible for regulating the onshore oil and gas industry, whereas the (federal) Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has the authority to regulate oil and gas production activities on federal lands. The EPA sets standards for air quality under the Clean Air Act but allows states, under most circumstances, to develop and implement the regulations necessary to meet the federal standards. In federal waters (typically outside three nautical miles of state waters), the federal government owns the resources and federal agencies regulate oil and gas activities, including the emissions associated with them. The situation is very similar in Australia. Offshore resources in Commonwealth waters (beyond three nautical miles) are regulated by a national regulator. The Clean Energy Regulator implements the Safeguard Mechanism, the government policy for reducing emissions from Australia’s industrial facilities, including oil and gas production, which emit over 100,000 tCO2e annually. State and territorial regulators (e.g., the Northern Territory) can set, and implement, more detailed regulations on flaring, venting, and methane emissions. Often, the oil and gas industry and environmental regulators collaborate, but there can be a “lead” regulator (e.g., the Environment Protection Authority in New South Wales).

In Canada, the federal Canadian Energy Regulator jointly regulates offshore resources with the Maritime Provinces (Labrador, Newfoundland, and Nova Scotia) and retains powers over so-called frontier areas (including the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Sable Island). In Argentina, the provinces own oil and gas resources, while legislative powers over general environmental matters are transferred to the federal government, which, through the General Environmental Law, implements minimum environmental standards countrywide, including for the oil and gas industry.

Building on the main pillars established in primary legislation, secondary legislation seeks to establish standards and guidelines for oil and gas production. The goal is to achieve environmental, safety, and health objectives while maximizing oil and gas recovery; avoiding wastage during production; and ensuring efficient delivery to market. Many jurisdictions have introduced detailed secondary legislation to reduce overall flaring and venting volumes; this has added flexibility and increased adaptability in response to the industry’s evolving conditions. Often, the same jurisdictions are early adopters of fugitive methane regulations. The measures include:

- Leak detection, mitigation, and reporting requirements for fugitive methane emissions

- Specifications of equipment and operating processes to ensure efficient combustion or replace equipment with high fugitive methane emissions

- Limits on the maximum permissible volume and duration of continuous flaring or methane intensity

- Specifications requiring gas flaring sites to be within safe distances from other facilities and populated areas

- Caps on heat and noise generation

- Limits on smoke and noxious odors generated by flaring.

Some jurisdictions, especially in North America and Europe, have been updating their gas flaring and venting regulations by incorporating adjustments to environmental legislation restricting GHG emissions. In Canada, the provincial governments of Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan have established flaring and venting regulations as resource owners, while the federal ministry, Environment and Climate Change Canada, has issued methane emission abatement standards for the whole country. Provinces can pursue their own regulatory or market-based approaches, provided they meet or exceed the federal targets (referred to as “equivalent regulations”). This approach has led Alberta and British Columbia to update their gas flaring and venting regulations, making them compatible with federal environmental legislation. Saskatchewan has yet to introduce additional regulatory measures to fulfill a new equivalency agreement before 2024.

In many jurisdictions, operational requirements for gas flaring and venting have either not been established sufficiently in secondary legislation or are not accompanied by the monitoring capacity needed for their enforcement. Given the large number of facilities and equipment to be considered, operational requirements for fugitive methane are still under development even in jurisdictions with detailed flaring- and venting-related regulations.

In countries without regulations specifically covering flaring and venting, confidential contractual or licensing arrangements between the government and the national oil company, on the one hand, and the operator, on the other hand, govern most relevant aspects. In Libya, for example, a committee comprising the national oil company’s and the operator’s representatives grapple with topics such as adherence to good oil field practices and the commercial assessment of associated gas when the context is a production-sharing contract. In fact, good oil field practice is fairly common language across jurisdictions. A related emission reduction standard is “as low as reasonably practicable” or ALARP, or similar language can also be found in different regulatory documents, licenses, or agreements.

Recommendations

- Primary legislation should explicitly address the treatment of associated gas for reducing flaring and venting, besides setting targets for mitigating fugitive methane emissions. These requirements will also help achieve local air pollution, safety, and health objectives; maximize resource recovery; and prevent wastage.

- Countries should adopt detailed secondary legislation that empowers regulators to monitor and enforce the reduction of flared, vented, and fugitive emission volumes through operational standards and guidelines, regular recordkeeping and reporting, and site inspections. The Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan provide excellent examples of dedicated pieces of stand-alone legislation that offer valuable lessons to other jurisdictions.

- When preparing legislation, key public and private sector stakeholders (e.g., enforcement agencies, civil society representatives, and recognized industry bodies) should be engaged in thorough public consultation and notified of updates; doing so can make laws and regulations more effective and create broad-based support, resulting in increased compliance.

Regulatory Governance and Organization

Institutional responsibilities for regulating gas flaring, venting, and fugitive methane are allocated in multiple ways. A clear definition of which institutions have regulatory authority over the industry, as well as the scope of these institutions’ mandates, is a necessity. The final institutional arrangements depend on resource ownership (federal, subnational, nonstate) and the nature of the regulation (oil and gas development and production, environmental, fiscal).

Despite the inherent risk of legal and regulatory overlaps, gas flaring and venting and fugitive emissions tend to be regulated by two authorities: one in charge of oil and gas and the other in charge of the environment. These authorities could be ministries, separate regulators, ministerial departments, or departments within national oil companies. The agencies responsible for oil and gas typically pursue abatement strategies from the perspective of waste prevention; some require the payment of royalties or fees for flared or vented gas. Some agencies have introduced fees for fugitive methane emissions. Environmental authorities have multiple responsibilities, including assessing the environmental impact of gas flaring and venting, and, increasingly, of fugitive methane emissions, especially within the context of climate change policies, and enforcing emission limits.

The enabling statutes of individual regulators should clearly define their specific responsibilities and powers, ideally allowing each to enforce compliance independently of the executive branch of the government and, if applicable, the national oil company. A framework that is widely accepted as being appropriate, is one under which the minister in charge of oil and gas is responsible for formulating policies and regulations and delegates monitoring and enforcement of compliance to the regulator. The level of delegation varies by country. In one country, the regulator may be empowered on a broad range of functions, whereas elsewhere, its role may be limited to a narrow set of technical and administrative activities, for example, keeping the registry of concessions and collecting fines from time to time but with little public disclosure. An upstream regulator regulating day-to-day operations, including flaring, venting, and fugitive emissions, from technical and commercial perspectives appears to be preferred in several jurisdictions.

Alberta’s provincial oil and gas regulator, the Alberta Energy Regulator, is a good example of a capable independent agency with full responsibility for all upstream oil, gas, and oil sands activities in the province, including flaring, venting, and fugitive methane. In line with the applicable laws and regulations, the agency’s operations cover regulatory applications and enhancements, compliance and liability management, geological surveys, and technical science and innovations.

The Colombian Ministry of Mines and Energy defines policy for the sector and is responsible for issuing technical rules and administrative decisions related to the regulation and imposition of applicable sanctions for noncompliance. The National Hydrocarbons Agency and the Ministry of Mines and Energy executed an interadministrative agreement that delegates certain inspection functions and regulatory activities to the National Hydrocarbons Agency, an autonomous entity under the Ministry of Mines and Energy with administrative and financial independence. The agency awards and negotiates exploration and production contracts and regulates any activity that it governs, including flaring authorizations, measuring standards, leak detection and repair (LDAR) requirements, and compliance monitoring.

Where environmental regulations are in place, alongside an environmental regulator under the supervision of a separate ministry responsible for the environment, it is important that all relevant authorities consult and cooperate regularly following preset procedures before issuing permits or approving oil field developments or emissions management plans. For example, in New South Wales, several agencies have different responsibilities with respect to the gas industry, but the Environment Protection Authority, which issues environment protection licenses, was appointed as the lead regulator for all gas activities in 2015.