Policy and Targets

Background and the Role of Reductions in Meeting Environmental and Economic Objectives

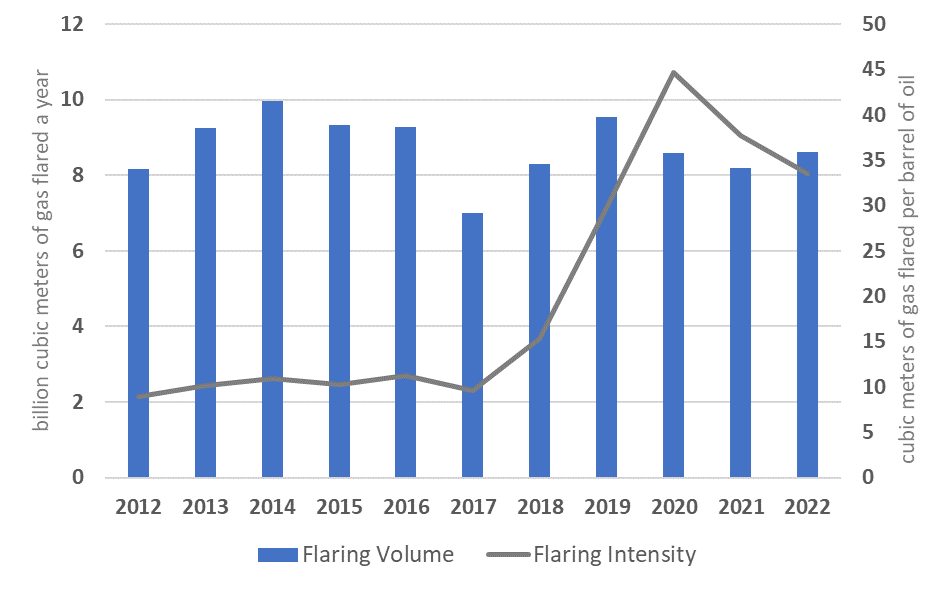

Between 2012 and 2022, the flaring intensity in the República Bolivariana de Venezuela increased by a factor of four—the largest increase among the countries studied. In 2022, its flaring intensity was 33.53 cubic meters per barrel of crude oil produced, the highest of all countries studied (figure 1). The declining trend in oil production was reversed in 2022; although flare gas volumes remained stable, there was a reduction in flaring intensity. There were 103 individual flare sites in the most recent flare count, conducted in 2022.

Figure 1. Gas flaring volume and intensity in República Bolivariana de Venezuela, 2012–22

The country submitted its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2018. It includes a national mitigation plan that aims to reduce emissions by at least 20 percent by 2030 compared with a scenario in which the plan is not implemented. The NDC cites projects by the national oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), to reduce flaring and venting by implementing associated gas utilization projects. These projects are reported to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by more than 500,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. The capture and use of methane emissions from the waste sector are listed as mitigation actions, but there are no further details.

More than 90 percent of the gas produced in the República Bolivariana de Venezuela is associated with crude oil production. Most of the flared gas comes from mature fields in the eastern part of the country and the Orinoco Belt. The routine flaring of gas by PDVSA in northern Monagas has become one of the largest sources of natural gas flaring in the world.

Targets and Limits

No evidence regarding targets and limits could be found in the sources consulted.

Legal, Regulatory Framework, and Contractual rights

Primary and Secondary Legislation and Regulation

Article 2 of the Organic Law on Hydrocarbons, 2006, states that activities related to natural gas are governed by the Organic Law on Gaseous Hydrocarbons, 1999, except for the extraction of associated gas, which is governed by the Organic Law on Hydrocarbons, 2006. These laws allow for gas exploration and exploitation operations by third parties, without PDVSA intervention, but with the obligation to sell the gas to PDVSA or other state companies at prices set by the government. Article 2 of the Organic Law on Gaseous Hydrocarbons, 1999, governs the collection, storage, processing, industrialization, transport, distribution, and internal and external commercialization of nonassociated and associated gas.

Other relevant laws and regulations include Regulation of the Hydrocarbon Law, 1943, Regulation on the Conservation of Hydrocarbons,1969, and Decree 638/1995, Norms on Air Quality and Control of Atmospheric Pollution, 1995.

Legislative Jurisdictions

Natural gas, including flared and vented gas, is a matter of national jurisdiction, as stated in Articles 1–3 of the Organic Law on Gaseous Hydrocarbons, 1999.

Associated Gas Ownership

The Constitution of the República Bolivariana de Venezuela,1999, Article 3 of the Regulation of the Hydrocarbon Law, 1943 , and Article 1 of the Organic Law on Gaseous Hydrocarbons, 1999 , vest all hydrocarbon rights in the state. Concessions grant companies the right to explore, develop, and exploit hydrocarbons. Article 21 of the Regulation on the Conservation of Hydrocarbons, 1969 , states that if the operator does not use the gas as specified in Article 20, the Ministry of Mines and Hydrocarbons (now the Ministry of Popular Power of Petroleum) may take it free of charge at the separator’s exit.

Regulatory Governance and Organization

Regulatory Authority

The Ministry of Popular Power of Petroleum (known as MinPetróleo) is the overarching policy and regulatory authority. The Ministry of Popular Power for Ecosocialism (Ministerio del Poder Popular para el Ecosocialismo [MINEC]) is the environmental policy and regulatory authority.

Regulatory Mandates and Responsibilities

MinPetróleo is in charge of formulating, executing, and evaluating the country’s oil and gas policies and regulating the industry. It supervises and controls the operations of the PDVSA and its subsidiaries, which the government owns. MINEC regulates emissions from oil and gas operations and is responsible for authorizing flaring and venting. It provides permission to flare on a case-by-case basis, in accordance with Decree 638/1995 , which stipulates air quality limits and permitted maximum air emission levels for controlling atmospheric emissions, including from flaring. Article 20 of Decree 1257/1996 requires the submission of an environmental impact assessment (EIA) based on a feasibility study and a production plan to MINEC for approval before a project’s commissioning.

Monitoring and Enforcement

Article 6 of the Organic Law on Gaseous Hydrocarbons,1999 and Articles 10, 14, and 16 of the Organic Law of the Environment, 2006, empower the regulator to monitor and audit the oil and gas operations for the protection of the environment.

Licensing/Process Approval

Flaring or Venting without Prior Approval

Article 121 of the Regulation of the Hydrocarbon Law, 1943 , establishes that excess gas that cannot be used or returned to the field can be flared. Only gas from wells with very low pressure is allowed to be vented. Vents must be high enough to facilitate the dispersion of gas without causing harm.

Article 40 of Decree 638/1995 states that MINEC may authorize trial periods for the initial operation of processes or equipment to control emissions. This authorization is granted in accordance with Article 21 of the Organic Law of the Environment, 2006 ; its duration is limited to six months or less. In cases of emergency or unforeseeable emissions in violation of the regulations, the operator must notify MINEC and activate its emergency contingency plans.

Authorized Flaring or Venting

Articles 20–23 of Decree 1257/1996 require operators to obtain environmental licenses before starting exploration or production. Applicants must submit to MINEC an EIA that describes their gas flaring and venting activities. After evaluation, MINEC may grant an environmental license for such activities. The license may contain specific requirements and emission reporting procedures for flaring and venting, which are set on a case-by-case basis. In addition, Decree 638/1995 requires a specific flaring permit to be sought from MINEC during operations.

Development Plans

No evidence regarding development plans could be found in the sources consulted.

Economic Evaluation

Article 20 of the Regulation for the Conservation of Hydrocarbons, 1969 , requires operators to take any reasonable measure, if economically justified, to use associated gas for any of the following purposes:

- maintenance of reservoir pressure in accordance with recognized technical procedures in the oil industry

- any internal, commercial, or industrial use, including its use as a fuel in the operator’s facilities

- injection into oil fields or other appropriate strata or underground storage, according to recognized technical procedures.

Article 22 states that any associated gas that cannot be utilized in the above ways must be disposed of in a manner that does not cause harm.

Measurement and Reporting

Measurement and Reporting Requirements

Article 13 of Decree 638/1995 states that the composition of emissions from flaring must be analyzed using a minimum of three samples at each selected collection point when the study is carried out for the first time and a minimum of two samples after that. The runs should be carried out when the production volume is greater than the annual average. Article 26 requires operators to submit details of the composition of their emissions to MINEC at least annually.

Article 28 of Decree 1257/1996 requires submission of an environmental supervision plan to MINEC for each project, together with a request for environmental authorization. In the case of hydrocarbons, the plan will be incorporated in the corresponding environmental impact study. The environmental supervision plan should include measures to mitigate the impacts of gas flaring and venting as well as the reporting of volumes and emissions.

Measurement Frequency and Methods

Article 6 of Decree 638/1995 specifies sampling period criteria (frequency, duration, and number of samples) to ensure compliance with air quality limits set in the decree. Carbon dioxide and methane emissions are not included in the decree, but sulfur dioxide, oxides of nitrogen, particulate matter, and other air pollutants are.

Engineering Estimates

Article 7 of Decree 638/1995 provides the analytical method, measurement period, and sampling method for each air pollutant covered by the decree. Sampling can be carried out either manually or automated via instruments. Analytical methods include automated approaches such as flame photometry and manual approaches such as colorimetry. MINEC may authorize other measurement methods if requested by the regulated party.

Record Keeping

No evidence regarding record-keeping requirements could be found in the sources consulted.

Data Compilation and Publishing

Both MinPetróleo and the PDVSA have published flaring data, with the last publication dating back to 2016.

Fines, Penalties, and Sanctions

Monetary Penalties

No information was identified in the current legislation specific to penalties for flaring or venting. However, noncompliance with the pollutant emission limits established in Decree 638/1995 can trigger sanctions per Articles 108–135 of the Organic Law of the Environment, 2006 . Article 108 states that financial penalties may be up to 10,000 tax units. Article 129 states that experts will determine the amount of damage, which will serve as the basis for sanctions and environmental measures.

The Environmental Penal Law, 2012, focuses on criminal behavior negatively affecting the environment and natural resources. Article 96 sanctions offenders with a monetary penalty of up to 2,000 tax units for emitting or allowing the escape of pollutants harmful to the environment.

Nonmonetary Penalties

Article 51 of the Organic Law on Gaseous Hydrocarbons, 1999 , empowers the MinPetróleo minister to suspend activities for up to six months, depending on the seriousness of the offense and the offender’s past performance. Articles 112 and 119 of the Organic Law of the Environment, 2006 , empower the responsible environmental authority to revoke licenses. Article 96 of the Environmental Penal Law, 2012 , provides for imprisonment of six months to two years for emitting harmful quantities of gas or allowing it to escape.

Enabling Framework

Performance Requirements

No evidence regarding performance requirements could be found in the sources consulted.

Fiscal and Emission Reduction Incentives

Article 104 of the Organic Law of the Environment, 2006 provides three types of economic or fiscal incentives, which could in principle be applied to flaring reduction:

- a state-financed credit system

- exemptions from the payment of taxes, fees, and contributions

- any other legally established economic or fiscal incentive.

These incentives will be granted to persons who invest in preserving the environment according to the terms established in Article 102. The incentives aim to promote the adoption of clean technologies, environmental management systems, conservation practices, and the sustainable use of natural resources, as stated in Article 103.

Use of Market-Based Principles

No evidence regarding the use of market-based principles to reduce flaring, venting, or associated emissions could be found in the sources consulted.

Negotiated Agreements between the Public and the Private Sector

No evidence regarding negotiated agreements between the public and the private sector could be found in the sources consulted.

Interplay with Midstream and Downstream Regulatory Framework

The Organic Law on Gaseous Hydrocarbons, 1999 , created the National Gas Entity (Ente Nacional del Gas) as a decentralized body, with functional, administrative, technical, and operational autonomy. The National Gas Entity reports to MinPetróleo and is responsible for coordinating the country’s gas development activities.

In 2002, PDVSA Gas, S.A. was established with the purpose of managing the commercial aspects of the country’s natural gas activities: exploration and exploitation of nonassociated gas; extraction, storage, commercialization, and distribution of liquefied petroleum gas; and transport, distribution, and marketing of natural gas. However, the domestic gas market is comparatively small, because electricity demand is met almost entirely by hydropower. Domestic gas prices are regulated at levels well below international prices, deterring the required investments in both associated gas and nonassociated gas development.