Policy and Targets

Background and the Role of Reductions in Meeting Environmental and Economic Objectives

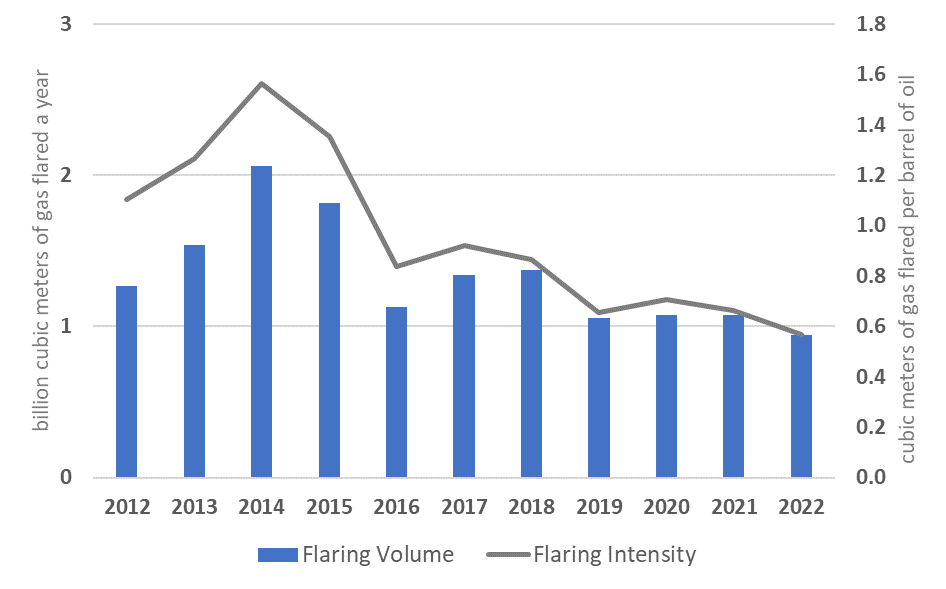

The volume of gas flared in Canada increased from 1.3 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2012 to 2.1 bcm in 2014 before falling to 0.9 bcm in 2022 (Figure 1). During this period, oil production rose by 45 percent, but associated emissions were more than offset by the decline in flaring intensity. There were 525 individual flare sites in the most recent count, conducted in 2022.

Figure 1. Gas flaring volume and intensity in Canada, 2012–22

Canada has considerable onshore and offshore resources. It produced 6 percent of the world’s crude oil and 4 percent of natural gas in 2019. Alberta, Saskatchewan, and offshore east coast sites accounted for about 50 percent, 30 percent, and 15 percent of Canada’s oil production, respectively. The growth of crude oil production since 2010 can be attributed mainly to increased output from the oil sands in Alberta. Natural gas production is concentrated in Alberta (nearly 70 percent) and British Columbia (nearly 30 percent). The great majority of oil and gas production occurs on state and private land, with the rest coming from federal and tribal lands.

In 2016, Canada endorsed the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 initiative. It also participates in the Global Methane Initiative, the Global Methane Pledge, and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition. In July 2021, Canada submitted an updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change that commits it to reducing GHG emissions by 40-45 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, raising the level of ambition substantially from the original NDC in 2016. There is an increased focus on reducing methane emissions from the oil and gas sector. Canada’s NDC outlines methane initiatives in individual provinces (see the case studies on Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan). The updated NDC is consistent with the federal government’s pledge of Canada’s reaching net-zero emissions economy-wide by 2050.

The country’s GHG emissions from the oil and gas sector have been increasing for several decades. However, nationwide emissions have stabilized since the mid-2000s, thanks to the replacement of coal-fired power generation with gas-fired generation and renewable energy. With the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, 2016, Canada committed to reducing methane emissions from the oil and gas industry by 40–45 percent by 2025. In 2018, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), a Canadian government agency, published Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) SOR/2018-66. In November 2022, the Government of Canada proposed to amend these regulations to achieve at least a 75 percent reduction in methane emissions from the oil and gas industry by 2030 relative to 2012.

Targets and Limits

The Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) SOR/2018-66, last amended on January 1, 2023, contain standards for extraction, primary processing, long-distance transport, and storage. The regulations apply to facilities producing or receiving more than 60,000 m³ annually of hydrocarbon gas, which includes methane and certain volatile organic compounds. Upstream oil and gas facilities are required to take the following actions, among others:

- Limit vented volumes to 15,000 m³ a year.

- Implement leak detection and repair, starting in 2020. Regular inspections will be required three times a year, and detected leaks are to be repaired within 30 days unless the facility is required to be shut down, in which case an action plan must be prepared and implemented.

- Conserve or flare gas instead of venting, starting in 2020.

In many instances, but especially in technical matters such as the measurement of gas volumes flared or vented, these federal regulations defer to provincial flaring and venting rules and emissions limits, which provincial regulators implement. Provincial emission limits must meet or exceed federal targets.

Legal, Regulatory Framework, and Contractual rights

Primary and Secondary Legislation and Regulation

The Canada Oil and Gas Drilling and Production Regulations, 2009, ban flaring and venting unless the federal energy regulator permits them or they are necessary because of an emergency. The Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act, 1999, governs the exploration, production, processing, and transport of oil and gas in marine areas controlled by the federal government. Provincial governments have specific legislation governing the exploration and production of oil and natural gas as well as flaring and venting.

The Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, regulates pollution prevention and waste management in matters of interprovincial or international application. Particularly relevant for flaring and venting from oil and gas operations are the Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) SOR/2018-66 . Provinces can choose to adopt these regulations or draft their own to meet or exceed the federal targets. Canada’s three major oil and gas provinces—Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia—have written their own rules.

The Offshore Waste Treatment Guidelines, 2010, help operators manage waste material associated with petroleum drilling and production in offshore areas. Two agreements between the federal and provincial governments—the Canada–Newfoundland and Labrador Atlantic Accord Implementation Act, 1987, and the Canada–Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Resources Accord Implementation Act, 1986—established two regulatory boards, the Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board and the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board.

The agreements also formalized principles of shared management of offshore oil and gas resources and revenue sharing from previous agreements, such as The Atlantic Accord–Memorandum of Agreement between the Government of Canada and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador on Offshore Oil and Gas Resource Management and Revenue Sharing, 1985, and the Canada–Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Resources Accord Implementation Act, 1986.

Many of the federal regulations have been adopted by Newfoundland, Labrador, and Nova Scotia. Examples include the following:

- Canada–Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Administrative Monetary Penalties Regulations, 2016

- Newfoundland Offshore Petroleum Drilling and Production Regulations, 2009

- Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Drilling and Production Regulations, 2009

- Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Administrative Monetary Penalties Regulations, 1987.

Legislative Jurisdictions

Canada’s federal and provincial governments share jurisdiction over energy and environmental policy and the legal and regulatory framework for upstream, midstream, and downstream operations. The provincial authorities enforce regulations and standard operating procedures for managing flaring and venting activities as well as reporting emissions (see the case studies on Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan).

Associated Gas Ownership

The ownership of oil and gas resources is split between the provincial government, the federal government, private freehold owners, and First Nations. Since 1887, the usual practice has been to reserve mineral rights in the granting of land. The Canada Petroleum Resources Act, 1985, governs the lease of federally owned oil and gas rights on “frontier lands,” including the “territorial sea” (12 nautical miles beyond the low water mark of the outer coastline) and the “continental shelf” (beyond the territorial sea). Under the act, subsurface oil and gas rights in unexplored areas are issued during a public call for bids, and the successful oil and gas company must pay royalties to the federal government. The rights to explore for, develop, and produce oil and gas, including associated gas, are then transferred to participants through licenses.

Regulatory Governance and Organization

Regulatory Authority

The Canada Energy Regulator (CER) was formed under the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, 2019, replacing the National Energy Board. It regulates the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Sable Island, submarine areas not within a province in the internal waters of Canada, and the territorial sea or continental shelf of Canada, as defined in the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act, 1999. The act provides a clear separation between the operational and adjudicative functions of the regulator.

The Canada–Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board is an independent agency that regulates petroleum-related offshore activities. The Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources part of the provincial government, regulates onshore petroleum-related activities. The Canada–Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board regulates oil and gas activities in the Canada–Nova Scotia offshore area. The Canada–Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board and the Canada–Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board jointly regulate oil production off the coast of the maritime provinces and set limits on the volumes of gas flared in offshore installations in their respective jurisdictions.

Canada’s constitution grants exclusive authority to the provinces to regulate mineral development within their boundaries. The major producing provinces have independent oil and gas regulators. Federal and provincial (as well as territorial and indigenous) governments share authority over environmental matters. Each province has its own environmental laws.

Regulatory Mandates and Responsibilities

The mandate, roles, and responsibilities of the CER include monitoring the companies operating oil and gas pipelines that cross a national, provincial or territorial border, and overseeing oil and gas exploration and activities not otherwise regulated. The ECCC reports to the federal government’s minister of the environment and is the lead environmental federal agency. The department delivers its mandate through acts and regulations, such as the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 . It sets the national ambient objectives for different air pollutants, including those from flaring and venting.

Depending on the jurisdictional and environmental nature of the oil and gas project, an environmental assessment may be required by the provincial government, the federal government, or both per the Impact Assessment Act, 2019. Each province has its own environmental permit regime, with the provincial regulator issuing these permits. Generally, approvals are required if any substance is released that could harm the environment.

Monitoring and Enforcement

The CER has powers to enforce regulatory compliance. It can conduct audits and inspections and has various enforcement powers, including the notification of noncompliance, the issuance of inspection orders and warnings, the imposition of administrative penalties, and prosecution. All of these measures are typically applied in relation to the severity of the violation and can be escalated if violators do not take correction actions as ordered by the CER. Provincial regulators have monitoring and enforcement powers that are more directly applicable to oil and gas operations in their provinces.

Licensing/Process Approval

Flaring or Venting without Prior Approval

The definition of “waste” in the Canada Oil and Gas Drilling and Production Regulations, 2009 , includes gas flared or vented when it could have been economically recovered and processed or injected into an underground reservoir. Section 67 states that no operator should flare or vent gas unless an emergency requires it to do so. The CER must be notified in the daily drilling report, daily production report, or any other written or electronic form. The notification should include the volume of flared or vented gas. The same provisions can be found in the Newfoundland Offshore Petroleum Drilling and Production Regulations, 2009 , and the Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Drilling and Production Regulations, 2009 .

Section 48 of the Processing Plant Regulations requires companies to report to the CER within one week of any flaring of hydrocarbon gas occurrence or a by-product of the processing of hydrocarbon gas that occurs as a result of an emergency. Section 6 of the CER Event Reporting Guidelines, 2018, defines an emergency as any situation in which emergency or contingency procedures, such as process upsets because of automated or manual emergency shutdowns, were used. Also reportable are flaring events that may have a significant adverse effect on property, the environment, or safety. Companies are not required to report nonroutine flaring, such as that resulting from regulator-required maintenance. Provincial regulators have more specific guidelines on flaring and venting that do not require permits (see the case studies on Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan).

Authorized Flaring or Venting

Section 5 of the Canada Oil and Gas Drilling and Production Regulations, 2009 (“Management System, Application for Authorization and Well Approvals”; see footnote 8), requires that the application for authorization be accompanied by information about any proposed flaring or venting of gas. This information should include the rationale, rate, quantity, and duration of the flaring or venting. Provincial regulators have more specific guidelines on applying for and obtaining flaring and venting authorizations.

Development Plans

Development plans are required and published on the Canada–Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board website. An example is the public review of the Hebron Development Plan Application.

Economic Evaluation

No evidence regarding economic evaluations by the federal government could be found in the sources consulted. However, provincial regulators consider the economic assessment of options to prevent or reduce flaring and venting.

Measurement and Reporting

Measurement and Reporting Requirements

Part 7 of the Canada Oil and Gas Drilling and Production Regulations, 2009 (“Measurements Flow and Volume”; see footnote 8), states that unless otherwise included in the approval, the operator should ensure the rate of flow and volume of any produced fluid that enters, leaves, is used, or is flared, vented, burned (incinerated)—or otherwise disposed of—are measured and recorded. This requirement encompasses any oil storage tanks, treatment facilities, or processing plants. The Newfoundland Offshore Petroleum Drilling and Production Regulations, 2009 , and the Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Drilling and Production Regulations, 2009 , have similar provisions.

The CER Event Reporting Guidelines, 2018 , require operators to submit an annual production report covering the previous year no later than March 31 of each year. This report must include details on the production forecast and gas conservation as well as efforts to maximize recovery and reduce costs. The report must also demonstrate how the operator manages or intends to manage the resource and avoid waste.

An annual environmental report must also be submitted. This report should include a summary of any incidents that may have had an environmental impact, discharges that had occurred and the waste material produced, and a discussion of the efforts undertaken to reduce pollution and waste material. The ECCC first developed the GHG reporting program in 2004. It has updated reporting and GHG quantification requirements several times. Compliance with the annual reporting of GHG is mandatory. All facilities emitting more than 10,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) in a given year must submit a report on their GHG emissions by June 1 of the following year. Facilities emitting less than the threshold can report voluntarily.

The Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) SOR/2018-66 include monthly reporting requirements to improve emissions estimates. They include inventories of emitting components at upstream facilities; reports on volumes of gas vented, flared, and delivered off-site; and results of leak-detection-and-repair inspections and monitoring.

Measurement Frequency and Methods

Under Sections 67 and 79 of the Canada Oil and Gas Drilling and Production Regulations, 2009, flows and volumes are reported through daily drilling and production reports. In an emergency, the CER should be notified of the volume of gas flared or vented in the daily drilling report, daily production report, or in any other written or electronic form as soon as the circumstances permit. Provincial regulators have their own reporting requirements, which in many cases are more detailed.

Engineering Estimates

No evidence regarding federal engineering estimates could be found in the sources consulted. However, provincial regulators provide detailed guidance on metering and estimation methodologies. The ECCC provides detailed instructions on how to calculate GHG emissions, including from flares and vents, in its periodically updated guidance.

Record Keeping

According to the Regulations Respecting Reduction in the Release of Methane and Certain Volatile Organic Compounds (Upstream Oil and Gas Sector) SOR/2018-66 , operators must maintain records that show that they have calibrated monitoring and leak detection devices. Provincial regulators provide detailed guidance on reporting and record-keeping requirements. Regulators may issue penalties for documents containing false or misleading information.

Data Compilation and Publishing

The National Pollutant Release Inventory is Canada’s legislated, publicly accessible inventory of pollutant releases. Its reports are published monthly and annually. Operators must prepare a complete inventory of pollutant release quantities and report emission sources to the National Pollutant Release Inventory if they exceed thresholds. Reporting is mandatory for facilities in the oil and gas sector that meet specified air contaminant threshold criteria. Reports for the previous year are due by June 1 of each year. Provincial energy and environmental regulators often have more detailed reporting on flared volumes and emissions available (see the case studies on Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan).

Fines, Penalties, and Sanctions

Monetary Penalties

No monetary penalties or fees relate explicitly to gas flaring and venting at the federal level (although provincial regulators can impose them). However, noncompliance with regulations and rules issued by the CER, which include reporting requirements on gas flaring and venting, can result in monetary penalties of up to Can$100,000 (about US$79,000 as of September 2021) a day per violation.

The violation of any specified provision of the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act, 1999 , or any of its regulations may result in a penalty. Such violations include failure to comply with any term, condition, or requirement of an operating license or authorization or any approval, leave, or exemption granted under the act. Under Paragraph (1)(b), the penalty for a violation should not be more than Can$25,000 (about US$20,000 as of September 2021) for an individual and Can$100,000 (about US$79,000 as of September 2021) for any other entity.

Canada Oil and Gas Operations Administrative Monetary Penalties Regulations (Federal-SOR/2016-25) establish administrative monetary penalties to provide regulatory agencies with an enforcement tool to complement other types of sanctions, such as notices of noncompliance, orders, directions, and prosecution. The process for imposing administrative monetary penalties is similar at both the federal and provincial levels. The CER website provides a record of the sanctions imposed via a downloadable spreadsheet and an interactive tool. Compliance measures reported include administrative monetary penalties and other measures.

The Environmental Enforcement Act, 2010, enhanced the enforcement tools and penalty regime by adding ranges for fines tailored to different offenses. It also introduced minimum fines and increased maximum fines for serious offenses. The Environmental Violations Administrative Monetary Penalties Act, 2009, details environmental administrative monetary penalties.

Nonmonetary Penalties

According to the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act, 1999 , the CER may suspend or revoke an operating license or an authorization for failure to comply with, contravention of, or default in respect of a fee or charge payable per the regulations made under Section 4 or a requirement undertaken in a declaration referred to in Subsection 5.11.

Enabling Framework

Performance Requirements

No evidence regarding federal performance requirements could be found in the sources consulted. However, provincial regulators provide detailed guidance on the performance of oil and gas operations, including flaring and venting.

Fiscal and Emission Reduction Incentives

Resource owners in Canada (the federal or provincial government, private freehold owners, or First Nations) generate revenues primarily through royalties and taxes paid to them by developers from selling extracted oil and gas. Royalties can be up to 45 percent in federal onshore and offshore fields. No evidence regarding federal fiscal and emission reduction incentives could be found in the sources consulted. However, provinces have fiscal incentive programs, such as royalty waivers to induce gas capture, thereby reducing flaring and venting (see the case studies on Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan).

Use of Market-Based Principles

In October 2016, the federal government published the Pan-Canadian Approach to Pricing Carbon Pollution, which established the federal benchmark for the 2018–22 period. In December 2016, Canada’s First Ministers adopted the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change , which required all provinces and territories to implement carbon pollution pricing systems by 2019. Under the federal legislation, the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, 2018, the federal government introduced a two-part carbon pricing scheme: a fuel charge and an output-based pricing system (OBPS). The fuel charge started with a carbon price of Can$10 (about US$7.9 as of September 2021) per tCO2e, increasing to Can$30 (about US$24 as of September 2021) in 2021 and Can$50 (about US$39 as of September 2021) by 2022. The federal benchmark is updated to have an initial carbon price of Can$65 (about US$47.8 as of May 2023) in 2023, and this price is to increase by Can$15 (about US$11) every year to reach Can$170 (about US$125) in 2030 . This price applies in all provinces that do not set their own prices.

The OBPS must be designed to encourage facilities to reduce their emissions. Performance standards must be set such that, at a minimum, the marginal price signal is equivalent to the federal benchmark. Provinces can set their emissions intensity standards. Facilities able to reduce their emissions below these standards are eligible for performance credits. The OBPS “must only apply to sectors that are assessed by the jurisdiction as being at risk of carbon leakage and competitiveness impacts from carbon pollution pricing.” The federal carbon pricing regime does not cover all industries. Methane emissions from the oil and gas value chain, for example, are not comprehensively addressed. Some provinces adopted the federal carbon pricing benchmark or introduced their own carbon tax, while others combined provincial fuel charges with the federal OBPS or vice versa. In all cases, provincial measures must be equivalent to the federal benchmark. Quebec and Nova Scotia have cap-and-trade systems, where the caps must be set consistent with the minimum carbon price.

In 2019, Canada began designing the GHG offset program to encourage the cost-effective reduction of domestic GHG emissions or GHG removal projects from activities not covered by carbon pricing. The government issues offset credits only to projects that produce real, quantified, verified, and unique reductions in GHG. This offset program could provide incentives for upstream oil and gas producers to invest in offset projects.

Negotiated Agreements between the Public and the Private Sector

No evidence regarding negotiated agreements between the public and the private sector could be found in the sources consulted.

Interplay with Midstream and Downstream Regulatory Framework

Market diversity and access are crucial considerations for the Canadian oil and gas industry. The Canadian natural gas market has been fully liberalized since gas prices were deregulated in 1985. Most oil and gas producers rely on pipelines and require provincial and federal policies that allow infrastructure to be built to deliver natural gas to new markets. A license from the appropriate provincial regulator must be obtained to construct and operate a pipeline. The CER, as the federal regulator, has jurisdiction if the pipeline crosses provincial or international boundaries. Federally regulated gas pipelines are generally considered to be contract carriers. The CER sets tariffs and the terms and conditions of access through regulation. The CER has the power to ensure that pipeline tolls are just and reasonable. Access to gas transmission is generally by agreement, but the CER has the power to direct a gas pipeline to provide any available capacity to a third party.