Policy and Targets

Background and the Role of Reductions in Meeting Environmental and Economic Objectives

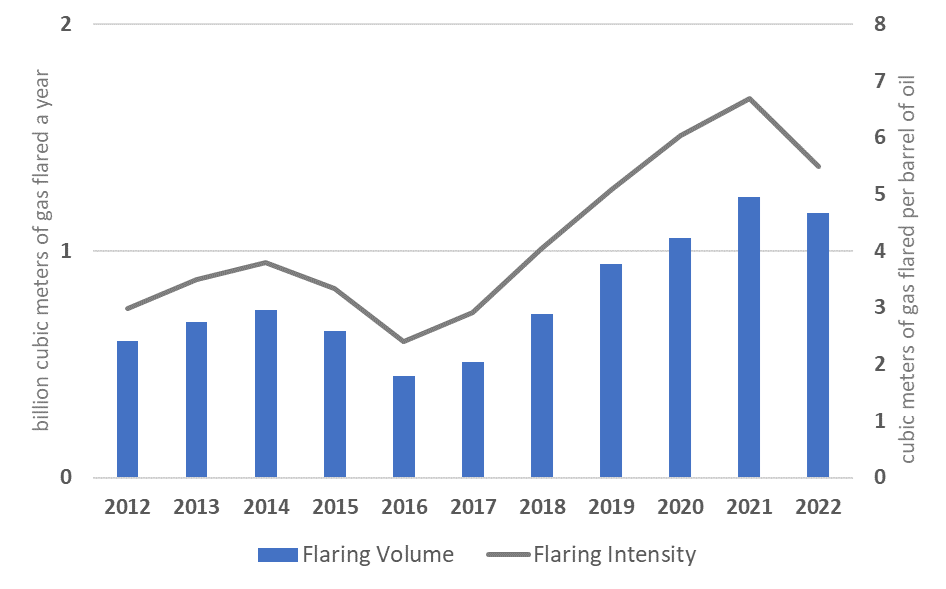

The volume of gas flared in Argentina doubled from 0.6 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2012 to 1.2 bcm in 2022 (Figure 1). During this period, oil production varied by about 10 percent with a significant uptick to 583,000 barrels a day in 2022. After broadly stabilizing in the first half of the 2010s, the flaring intensity increased steadily after 2017, reaching the highest level in 2021 and dropping again slightly in 2022. There were 156 individual flare sites in the most recent flare count, conducted in 2022.

Figure 1. Gas flaring volume and intensity in Argentina, 2012–22

Argentina participates in the Global Methane Initiative (n.d.) and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition. It submitted its first NDC in 2016 and its second in 2020. In its second NDC, Argentina committed not to exceed net emissions of 359 million tCO2e by 2030. This new goal is 26 percent lower than the target in the 2016 NDC. It represents an emissions reduction of 19 percent by 2030 from the 2007 peak emissions level.

Argentina participates in the Global Methane Initiative, the Global Methane Pledge, and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition. It submitted its first NDC in 2016 and its second in 2020. In its second NDC, Argentina committed not to exceed net emissions of 359 million tCO2e by 2030. At the end of 2021, Argentina updated its second NDC target to 349 million tCO2e by 2030. This new goal is 27.7 percent lower than the target in the 2016 NDC. It represents an emissions reduction of 21 percent by 2030 from the 2007 peak emissions level. The NDC does not specifically mention gas flaring or venting.

Most of Argentina’s oil and gas production is in Patagonia. The province of Chubut produces most of the oil. About half of the country’s natural gas comes from the Neuquén Basin, which is home to unconventional reserves, including the Vaca Muerta formation, which stretches across four provinces: Neuquén, La Pampa, Mendoza, and Rio Negro.

Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF) is the country’s largest producer of oil and gas. In the 1990s, 80 percent of YPF was privatized. YPF relinquished some upstream areas and entered into joint ventures with private operators for its most productive blocks. The state subsequently sold its remaining 20 percent stake to the Spanish oil company Repsol. However, the government retained veto power over crucial decisions.

In the gas sector, another state-owned company, Gas del Estado, was also privatized and unbundled into two gas transport and eight gas distribution companies. In 2012, through Law 26.741, 2012, the government expropriated a 51 percent controlling stake in YPF. Subsequently, the government promoted public-private partnerships with the renationalized YPF, with the primary goal of addressing Argentina’s energy shortages.

YPF committed itself to reducing its carbon dioxide emissions intensity by 10 percent by 2023. It will achieve this reduction through more efficient energy management, reductions in flared and vented gas, electrification and digitization of its operations, and adoption of low-carbon energy sources.

Targets and Limits

Section 3 of Annex 1 of Resolution No. 143/1998, sets out limits on and requirements for gas venting at the federal level. Gas venting from production wells is allowed if the gas-to-oil ratio at the venting point does not exceed the maximum limit of 1 m³ of gas per m³ of oil as of January 1, 2000. Section 3 prohibits venting in all wells in which the gas-to-oil ratio exceeds 1,500 m³ of gas per m³ of oil, regardless of the composition of the gas produced. These wells should remain shut if the conditions for the capture and use of the gas have not been resolved with the authorities.

Legal, Regulatory Framework, and Contractual rights

Primary and Secondary Legislation and Regulation

Section 7 of Annex 2, on model contracts, of Decree No. 1.443/1985, issued by the Federal Executive Power (Poder Ejecutivo Nacional), prohibits flaring or venting of gas except as authorized by the application authority. Resolution No. 105/1992 regulates flaring and venting standards and procedures to protect the environment during hydrocarbon exploration and production. The resolution states that associated gas with carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, or hydrogen sulfide can be flared. Noncombustible gas produced (carbon dioxide) can be vented. Resolution No. 143/1998 , replacing Resolution No. 236/1993, requires that unused gas be burned, allows venting only when burning is technically infeasible, and sets venting limits and requirements. Certain provinces have issued specific rules governing flaring and venting; others apply the Energy Secretariat’s standards in the above resolutions.

The federal Hydrocarbons Law No. 17.319, 1967 (Hydrocarbons Law, 1967 hereafter)—as amended by Law No. 26.197, 2006, and Law No. 27.007, 2014, among others—regulate oil and gas exploration, development, and production. The 2007 transfer of the domain of oil and gas areas to provinces limited the federal government’s power in the hydrocarbon industry’s design and management. Law No. 27.007, 2014, reinstated to the federal government some of its prerogatives by restricting provincial rights. The main aims of the 2014 amendments were to reverse declines in production, increase imports of hydrocarbons, and boost exploration and production, especially of unconventional resources. The law distinguishes between exploration permits for conventional and unconventional hydrocarbons and between exploration in the territorial sea and continental shelf. Law No. 26.659, 2011, as amended by Law No. 26.915, 2013, regulates offshore exploration and production activities.

Some provinces have issued specific legislation for the oil and gas sector; others have adopted the federal standards in their respective laws. In the Neuquén province, Law No. 1.926, 1991, and its associated regulation Provincial Decree No. 2.247/1996, establish and define the responsibilities of the Provincial Secretariat of Energy and Mining (currently the Undersecretariat of Energy, Mining, and Hydrocarbons) as the authorizing and enforcement authority for oil and gas activities. The Neuquén province—which issued Hydrocarbons Law No. 2.453, 2004, and the associated regulation, Provincial Decree No. 3.124/2004—established the framework for the exploration, production, industrialization, transport, and marketing of hydrocarbons and their by-products.

Hydrocarbons Law XVII-102, 1973, reaffirms that Chubut has complete administrative control over the hydrocarbon deposits located in the province. Hydrocarbons Law No. 2.727, 2004, reaffirms that Santa Cruz has complete administrative control over the hydrocarbon deposits located in the province. Provincial Law No. 4.296 reaffirms that Rio Negro has complete administrative control over the hydrocarbon deposits located in the province, including near coastal areas. These provincial laws are within the framework of federal Law No. 17.319, 1967 , and Law No. 26.197, 2006 .

Article 41 of the 1983 National Constitution transfers legislative powers with respect to general environmental matters from the provinces to the federal government. At the federal level, general legislation containing minimum environmental protection standards, such as Law No. 25.675 General Environmental Law, 2002, govern the oil and gas sector. Resolution No. 25/2004 defines the technical characteristics, structure, and scope of environmental studies and annual environmental monitoring reports to be submitted by oil and gas companies pursuing exploration and exploitation activities. In 2019, the National Congress passed Law No. 27.520, 2019, which set minimum standards for climate change adaptation and mitigation. The provinces are empowered to supplement the federal environmental regulations with local regulations, provided they do not overstep the established principle of federal law primacy. Several provincial regulations for controlling gaseous emissions have been passed in connection with environmental matters. For example, Law No. 2.175/1997, and its associated regulation Neuquén Provincial Decree No. 29/2001 regulate environmental protection and health issues associated with natural resources development in the Neuquén province.

Legislative Jurisdictions

Argentina has a highly decentralized federal system of government in which provinces play a significant role. Law No. 26.197, 2006 , which amended the Hydrocarbons Law, provides that the oil and gas fields belong to the federal government or the provinces in which the fields are located. Provincial governments are responsible for granting exploration permits and production concessions, enforcing laws and regulations, and administering the oil and gas fields. Law No. 27.007, 2014, prescribes that provincial governments are responsible for offshore oil and natural gas resources up to 12 nautical miles. Hydrocarbon deposits found within 12 nautical miles of the continental shelf’s outer limit are the federal government’s responsibility.

However, the provincial administrative powers must be employed within the framework of the Hydrocarbons Law and its regulations. This requirement means that the power to define the oil and gas policy and pass legislation remains with the federal government and Congress. The primary laws and regulations governing flaring and venting are federal. However, the 2022 National Plan for Adaptation and Mitigation of Climate Change calls for the strengthening of provincial authorities’ ability to identify, monitor, and control operational emissions from flaring and venting, and fugitive greenhouse gases and methane from the upstream sector.

Associated Gas Ownership

Hydrocarbons are exploited primarily via concessions. At the federal level, Article 6 of the Hydrocarbons Law, 1967 , states that licensees obtain the rights to extracted hydrocarbons and can transport and commercialize them, complying with the regulations issued by the executive power. Article 63 states that no royalties will be imposed on hydrocarbons used by the licensee. The royalty rate was 12 percent in 2019. With the approval of the Undersecretariat of Hydrocarbons, the licensee may determine the destination and conditions for the use of the gas.

In the case of the Neuquén province, Article 6 of Hydrocarbons Law No. 2.453, 2004 , states that the license holders will obtain the rights to the hydrocarbons they extract. As a result, they have the right to process, transport, and commercialize extracted hydrocarbons and their derivatives, subject to compliance with the regulations issued by the provincial executive power.

Regulatory Governance and Organization

Regulatory Authority

Gas flaring and venting are regulated at the federal and provincial levels. The federal regulatory authority is the Undersecretariat of Hydrocarbons (Subsecretaría de Hidrocarburos), part of the Federal Energy Secretariat (Secretaría de Gobierno de Energía). The federal regulatory authority for natural gas is the Energy Secretariat. Decree No. 7/2019 created the Ministry of Productive Development and placed the Energy Secretariat under its authority.

Each oil- and gas-producing province has its own regulator, governed by the Hydrocarbons Law, 1967 , and by provincial legislation and regulations. The regulatory authority is the Undersecretariat of Energy, Mining and Hydrocarbons, under the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources in Neuquén, the Ministry of Hydrocarbons in Chubut, the Energy Institute in Santa Cruz, and the Energy Secretariat in Rio Negro.

Regulatory Mandates and Responsibilities

At the federal level, authorization and enforcement for flaring and venting are the responsibilities of the Energy Secretariat. At the provincial level, the regulators listed in the previous section authorize flaring or venting and enforce related regulations. The Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development is responsible for establishing the minimum environmental protection standards for the sustainable management of the environment, preserving and protecting biological diversity, and implementing sustainable development. Decree No. 2.656/1999 clarifies that the “permitting authority” supervises and inspects the operational aspects of the oil and gas activities. By contrast, the environmental authority, the Undersecretariat of the Environment, enforces the environmental aspects.

Monitoring and Enforcement

Law No. 26.197, 2006 , grants the following powers to the provinces:

- complete control over all activities related to the supervision and control of the exploration permits and production concessions

- enforcement of all applicable legal and contractual obligations regarding investments, production, provision of information, and surface fee and royalty payment

- extension of legal and contractual terms

- issuance of sanctions detailed in the Hydrocarbons Law, 1967 .

Federal Resolution No. 143/1998 , Provincial Law No. 2.175/1997 , and Neuquén Provincial Decree No. 29/2001 fully empower the regulators to monitor and audit the oil and gas industry.

Licensing/Process Approval

Flaring or Venting without Prior Approval

Resolution No. 143/1998 prescribes that gas be flared, not vented, through appropriate procedures. If, for technical reasons, the gas cannot be flared, the operator is required to submit a report to justify venting.

Annex 1 (“Norms and Procedures for Venting Gas”) lists the circumstances under which gas venting is allowed:

- section 3.1 permits flaring or venting when the gas-to-oil ratio at the vent point does not exceed 1 m³ of gas per 1 m³ of crude oil produced.

- section 4.4 permits periodic venting of gas when there are no conduction lines to capture the gas at the wellhead.

- section 5.1 permits venting when it occurs during well testing.

The authorities should be notified in writing of all flaring and venting for all causes (maintenance, operations, or emergencies) within 24 hours. The reasons for the contingency, flow rates and damages, and the immediate measures and corrective measures implemented must be detailed.

The Neuquén province’s Law 2.175/1997 prohibits gaseous emissions from oil and gas wells. Emissions from flares can be authorized for oil wells if the emissions are not characterized as a hazardous waste. Article 2 of Neuquén Provincial Decree No. 29/2001 requires the operator to submit a report documenting a justification for venting if the unused gas cannot be flared for technical reasons and to follow the same criteria for venting as stipulated in Resolution No. 143/1998.

Authorized Flaring or Venting

Article 4 of Resolution No. 143/1998 requires the operator to submit a request for exemption to the undersecretary for breaching the permitted limits. Annex 1 of the resolution describes the procedure for submitting such a request. The regulator has 90 days from the date of receipt of the request to issue the approval or rejection of the request. Every request for an exemption must demonstrate for each reservoir the technical reasons for exceeding the limits and the maximum flow rate of gas to be flared or vented. The documentation and data should be updated every six months by May 31 and November 30 of each year in which exemptions are requested.

Section 3 of Annex 1 of Resolution No. 143/1998 states that the Energy Secretariat may judge whether venting should be reduced, either temporarily or permanently, on a case-by-case basis. Section 3 requires allowed venting to follow appropriate procedures and minimize the emissions of harmful gases into the environment. Section 3 also states that Sections 3, 4, and 5 of Resolution No. 105 should be followed in all cases. The Neuquén province’s Decree No. 29/2001 outlines the same criteria as Resolution No. 143/1998.

Development Plans

No information specific to requiring a development plan for associated gas as part of the field development approval for greenfield projects was identified. However, Federal Resolution No. 105/1992 requires the operator to prepare an EIA for the development phase. The EIA must specify the installations to manage associated gas or dispose of it after a technical-economic study confirms that its use is not viable. Article 20 of the Neuquén province’s Decree No. 2.656/1999 outlines norms and procedures regulating environmental protection during oil exploration and production similar to those in Resolution No. 105/1992.

Economic Evaluation

Resolution No. 143/1998 , subsection 5 of Annex 1 (“Norms and Procedures for Venting Gas, Section 5, Reasons for Exception–Gas Venting”), requires a technical and economic feasibility study in cases in which gas at the venting point has a high content of inert or toxic gases and the gas-to-oil ratio in each well is less than the 1,500 m³ of gas per m³ of oil, the limit stipulated in Section 3.2. The study should include analysis of the effects of the flow rate and total volume of vented gas. This analysis should demonstrate that neither the flow rates nor the volumes to be vented will reduce the exploitation of the gas. The study should include the flow rates and composition of the vented gas and the disposal method for each type of toxic gas produced. The Neuquén province’s Decree No. 29/2001 sets the same criteria as Resolution No. 143/1998.

Measurement and Reporting

Measurement and Reporting Requirements

Section 6 of Annex 1, on norms and procedures for venting gas, of Resolution No. 143/1998 covers flow rate measurement and registering. It requires the establishment and implementation at each venting point of a system to measure and record the flow of flared or vented gas and its composition in all cases. Article 14 of the Neuquén province’s Decree No. 29/2001 includes similar requirements.

Measurement Frequency and Methods

Per Resolution No. 143/1998 , flaring and venting of gases should be reported monthly to the authorities, including the location of the installation, flow rate, composition, causes of flaring or venting, measurement points, and points of emission. Article 7 of the Neuquén province’s Decree No. 29/2001 requires monthly submission of an affidavit (sworn declaration) documenting all gas emissions from oil wells. The original documentation of the sworn declaration should be submitted to the Provincial Directorate of Hydrocarbons and Fuels within 10 calendar days of the end of the month being reported.

Engineering Estimates

Subsection 6 of Annex 1 (on norms and procedures for venting gas) of Resolution No. 143/1998, which applies nationally, allows estimation of flow rates based on the last determination of the gas-to-oil ratio and the gas composition in the well when the gas is released to unblock a pump.

Record Keeping

Section 6 of Resolution No. 143/1998 , states the records should be kept on an annual basis. Article 14 of the Neuquén province’s Decree No. 29/2001 requires flaring and venting records to be retained for five years, not the one year required nationally.

Data Compilation and Publishing

Data on oil and gas production and disposition, including vented volumes of gas, are compiled at the national level and posted on a governmental website. The information can be filtered by province, year, concession area, and month. Information on vented gas volumes, which can be found in the “Gas Balances” file, has been compiled since 2009.

Fines, Penalties, and Sanctions

Monetary Penalties

Aside from penalties for general violations of the laws, regulations, and technical provisions, no specific monetary penalties for flaring or venting were identified. Article 87 of the Hydrocarbons Law, 1967 , sets fines for failure to comply with any of the obligations arising from authorizations and concessions that do not constitute causes for revocation. Decree No. 488/2020 introduces a new formula for calculating the fines in its Article 10. The fines vary with the severity and incidence of the breach, ranging from a minimum equivalent to the value of 22 m³ of national crude oil in the domestic market to a maximum of 2,200 m³ of the national crude oil in the domestic market for each violation.

Article 6 of the Neuquén province’s Law No. 2.175/1997 subjects emissions of unauthorized associated gas above the limits established in Article 5 to monthly payments. Article 2 of the Neuquén province’s Decree 29/2001 takes only the volume of gases released into account to calculate the rate to be charged for gas venting. Since December 31, 2001, these volumes have been set per cubic meter of gas flared or vented, beginning at 500 percent of the weighted average sales price of natural gas at the custody transfer point. Article 8 states that noncompliance with the limits imposed on associated gas from oil wells is subject to fines, based on the gravity of the offense, determined by the quality and quantity of the gas. The frequency of payments is monthly.

A newspaper article dated September 21, 2018, indicates that a provincial regulator, the Secretaria de Energía de Rio Negro, imposed a penalty on the national oil company, YPF, for venting rather than flaring. The fine was Arg$134,000 (about US$1,350 as of September 2021), following the formula introduced in Decree No. 488/2020 . YPF tried to reverse the fine by appealing to the Civil Chamber of Cipolletti. The ministry stated that YPF had committed 11 infractions since the renegotiation of its oil contracts, when it had agreed to make sizable investments in its facilities to avoid venting gas. No evidence could be found in the sources consulted as to whether the provincial government had collected any of the fines.

Nonmonetary Penalties

Section 9 of Resolution No. 143/1998 on inspections and sanctions, cites noncompliance with it as a sufficient reason for revoking the corresponding authorizations, except where the Energy Secretariat deems the noncompliance justified. Section 9 sets out the appeal process. Any transgression of the resolution will make the concessionaire or permit holder liable to the sanctions imposed in Law No. 17.319, 1967, under the law’s Titles VI and VII. The Energy Secretariat may request the revocation of the concession or exploration permit granted in the event of the assumptions outlined in Article 80 of the law.

Enabling Framework

Performance Requirements

No evidence regarding performance requirements could be found in the sources consulted.

Fiscal and Emission Reduction Incentives

Section 8 of Annex 1 of Resolution 143/1998 states that as a condition for granting the exception to gas venting, the licensees must provide a guarantee of investments in emission abatement within 15 calendar days from the notification of the approval to the company. The amount of the guarantee depends on the emission flows during the exception period and the abatement investments to be made. Guarantees are set for each project by semester or as a fraction of the exception period and of the investment to be made. The guarantee will be called if the company does not execute the agreed investments for each project at the expiration of each term.

Use of Market-Based Principles

According to the Fourth Biennial Update Report to the UNFCCC in 2021, there were 58 projects registered with carbon markets, 46 of them under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). However, there were no new projects under CDM between 2016 and the publication of the 2021 report, while projects registering in voluntary markets had increased. Most of the energy projects centered on wind, solar, hydro, and biomass power generation; several captured and used methane emissions from the waste sector.

YPF has two projects registered under the CDM, intended to reduce emissions in the La Plata and Luján de Cuyo industrial complexes. Combined, the two projects avoided about 168,687 tCO2 emissions in 2019. YPF also engages in carbon offset programs, such as reforestation in the Neuquén province. Started in 1998, these efforts sequestered an estimated 760,000 tCO2e over the course of 30 years.

Negotiated Agreements between the Public and the Private Sector

YPF has committed to minimizing gas, flared and vented, in compliance with the requirements established in Federal Resolutions No. 236/1993 and No. 143/1998 . Through its innovation department, YPF is developing two pilot projects that seek to eliminate gas flaring and venting. One project, implemented in the Bajada de Añelo area, compresses captured associated gas to make CNG. The second project, carried out in a partnership with Galileo, involves an on-site mini-plant that liquefies the gas, which is transported in cryogenic tanker trucks. After ten liquefaction plants were installed in 2017 to capture gas at seven wells in Neuquén and Mendoza, 150,000 m³ of gas were supplied daily for power generation.

Interplay with Midstream and Downstream Regulatory Framework

Natural gas provides more than 60 percent of power generation and more than half of the total energy consumed. Law No. 24.076, 1992, known as the Natural Gas Law, established the basis for deregulation of natural gas transport and distribution industries. The Federal Gas Regulatory Authority, created in 1992 by Decree No. 2255/92, oversees the transportation and distribution of natural gas.

Natural gas prices are a mix of regulated and market prices. Before the 2015 energy reform, domestic oil and gas prices were significantly lower than those at trade parity, and public services tariffs did not cover operational costs. The domestic supply of oil and gas was insufficient to meet demand. After 2015, domestic oil and gas prices started to align with international levels. Resolution No. 46-E/2017, as amended by Resolutions No. 419/2017 and 12/2018, introduced producer subsidies to attract investments in unconventional natural gas reservoirs in the Neuquén Basin. A minimum price of US$7.50 per million British thermal units (mmBtu) was guaranteed during 2018, decreasing by US$0.50/mmBtu a year to US$6/mmBtu by 2021. On December 31, 2021, the program was to end, at which point prices were expected to match import-parity values.

Law No. 26.197, 2006 , vests the federal government with the authority to grant concessions for interprovincial and export transport. Transport concessions located within the territory of only one province and not connected to export facilities were transferred to the provinces. Operators of pipelines and other transport and distribution infrastructure are required to provide open access to third parties if they have available capacity. Third parties have the right to access this transport infrastructure if they comply with the relevant procedures.

The growth of natural gas production will require substantial new investment in infrastructure and export routes in the near and medium term as well as cost-effective production and transport systems. The federal government launched a public tender for constructing and operating a new gas pipeline from the Vaca Muerta area in Neuquén to Saliqueló, south of Buenos Aires. Construction is underway.