Policy and Targets

Background and the Role of Reductions in Meeting Environmental and Economic Objectives

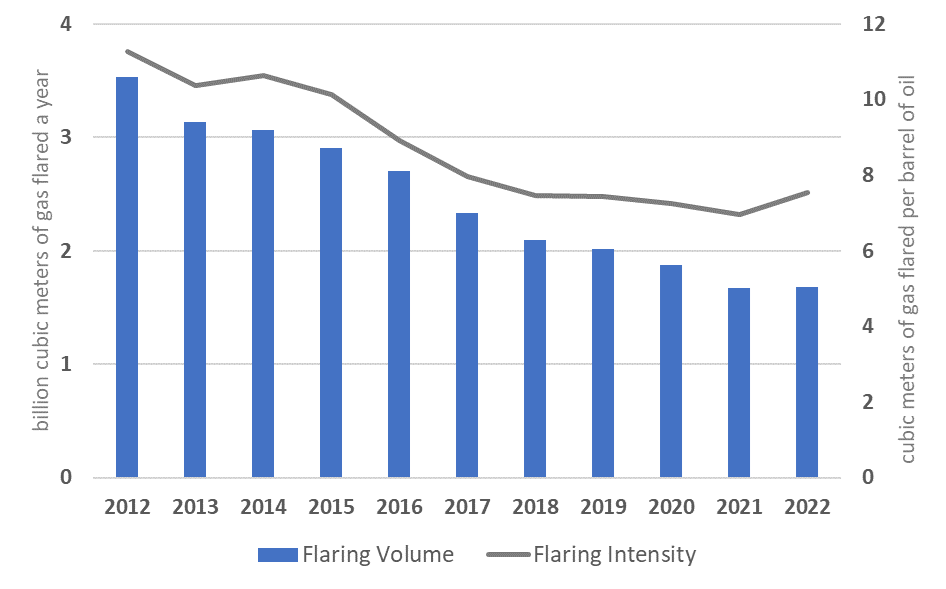

The volume of gas flared in Indonesia decreased from 3.5 billion cubic meters in 2012 to 1.7 billion in 2022 (Figure 3). The rate of decline was much greater than for oil production, which fell by almost 30 percent during the period. The flaring intensity correspondingly followed a generally declining trend, with a slight uptick in 2022. There were 189 individual flare sites in the most recent flare count, conducted in 2022.

Figure 3 Gas flaring volume and intensity in Indonesia, 2012–22

Indonesia endorsed the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 initiative in 2017. It also participates in the Global Methane Initiative and the Global Methane Pledge. In September 2022, Indonesia submitted an updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change that committed it to an unconditional reduction of 32 percent (up from 29 percent before the update) and a conditional reduction of 43 percent (up from 41 percent) in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030 relative to its business-as-usual scenario. The NDC does not mention flaring or venting. Methane capture is mentioned as an action only for the waste sector.

In 2010, the government launched the Indonesia Climate Change Sectoral Roadmap, an initiative to incorporate the climate change agenda in the country’s development plan. In 2012, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (Kementerian Energi Dan Sumber Daya Mineral [ESDM]) issued specific flaring regulations to optimize resource utilization and reduce flaring and GHG emissions. Building upon these efforts, in 2017 the government issued the National Energy Strategy, which outlines a transition to a cleaner, more climate-smart energy sector.

Targets and Limits

No evidence regarding sector-wide targets and limits could be found in the sources consulted. However, Indonesia does set operational limits on flaring (see section 10 of this case study). Its NDC and the Indonesia Climate Change Sectoral Roadmap set targets to reduce economywide GHG emissions.

Legal, Regulatory Framework, and Contractual rights

Primary and Secondary Legislation and Regulation

Articles 2 and 3 of the 2001 Oil and Gas Law, Law 22/2001, cover the environmental considerations relevant to the country’s oil and gas industry.

Ministerial regulation ESDM 17/2021, which replaced ESDM 31/2012, regulates gas flaring. It assigns overall flaring responsibility to the ESDM and its directorate, the Directorate General of Oil and Gas (DG Migas). All existing flaring activities must comply with the new regulations within two years.

The primary objective of ESDM 30/2021, which replaced ESDM 32/2017, is to optimize resource use by regulating the use and price of otherwise flared gas. Flare gas sale and purchase agreements signed and prices agreed upon before the enactment of this regulation remain valid until the relevant contracts’ expiration date.

Government Regulation 35/2004, issued by the president of Indonesia, regulates business activities related to the upstream oil and gas sector without any specific mention of flaring or venting. Although not directly aimed at flaring and venting of associated gas, several regulations lay the foundations for the pricing of gas sold to other sectors:

- Government Regulation 36/2004 regulates gas use in the downstream sector, defined as processing, transport, and storage of gas.

- Ministerial regulations ESDM 58/2017 and ESDM 14/2019 establish the pricing mechanisms for gas transported by pipeline sold on the domestic market.

- Ministerial regulation ESDM 45/2017 covers the use of gas for electricity generation, such as volume allocation for national purposes (Article 3) or price setting, for which Article 8 of the amendment ESDM 10/2020 provides numerical updates.

Legislative Jurisdictions

Gas flaring is a matter of national jurisdiction.

Associated Gas Ownership

Article 6 of Law 22/2001 and Article 24 of Government Regulation 35/2004 state that ownership of gas remains entirely with the government until the point of delivery, when the contractor assumes ownership of cost oil and gas and the contractual share of profit oil and gas. Ownership of gas not sold, including associated gas, remains with the government. Gas-related business activities, including the transfer of ownership, are covered in cooperation contracts, a type of agreement specific to Indonesia that closely follows the industry practice established for production-sharing contracts.

Regulatory Governance and Organization

Regulatory Authority

Articles 1 and 16 of ESDM 17/2021 assign overall responsibility and approval powers for flaring permission and reporting activities to the ESDM and DG Migas. According to Article 1(20) (also, Article 1[11] of ESDM 30/2021; see footnote 7]), a special work unit (Satuan Kerja Khusus Pelaksana Kegiatan Usaha Hulu Minyak dan Gas Bumi [SKK Migas]) is responsible for managing upstream oil and gas activities under the guidance and supervision of the ESDM. According to Article 1(21)—and also, Article 1(12) of ESDM 30/2021—Aceh Oil and Gas Management Agency (Badan Pengelola Migas Aceh [BPMA]) has joint responsibility for managing upstream oil and gas activities in the Aceh territory, including within 12 nautical miles of coastal waters.

Regulatory Mandates and Responsibilities

Flaring-related responsibilities are divided between the ESDM (including DG Migas) and SKK Migas. The ESDM sets the policy direction and DG Migas formulates and implements policies and technical standards (Article 1 of ESDM 17/2021; see footnote 5). Contractors must submit a request for the utilization and price of flare gas to SKK Migas or BPMA (Article 3 of ESDAM 30/2021; see footnote 7). SKK Migas or BPMA then submit the request to the minister, with recommendations. The minister (DG Migas) evaluates the application, seeking input from relevant agencies (Article 4). According to ESDM 45/2017 , in combination with the amendment in Article 8 of ESDM 10/2020 , the ESDM is also responsible for overseeing natural gas used in electricity generation.

Monitoring and Enforcement

Under ESDM 17/2021 and ESDM 30/2021 , authority is assigned to DG Migas, SKK Migas, and BPMA to supervise oil and gas operations, including flaring. Specific functions are discussed in relevant sections of this case study.

Licensing/Process Approval

Flaring or Venting without Prior Approval

Article 4 of ESDM 17/2021 lists the circumstances for and types of flaring events: routine, nonroutine, safety, emergency, instances when impure gas exceeds a 50 percent share, and flaring due to commercialization issues. Article 7 of ESDM 17/2021 lists the activities that qualify for nonroutine flaring; these include exploration and appraisal drilling, well testing and maintenance, and pressure relief. Article 9 requires contractors to make efforts to stop flaring in case of emergency situations or when safety is at risk. Processing business permit holders must make efforts to stop flaring during maintenance activities such as depressurizing. These efforts must be reported to DG Migas in writing, along with a plan to stop flaring and mitigate a recurrence through preventative efforts.

In case a single flaring incident lasts more than a day and exceeds an average daily volume of 20 million standard cubic feet (mmscf), contractors with processing business permits must report online to the chief inspector within 24 hours of the incident and a written report must be submitted to DG Migas within seven days after the end of the incident (Article 6 of ESDM 17/2021).

Authorized Flaring or Venting

Article 5 of ESDM 17/2021 sets DG Migas–authorized routine gas flaring volume limits of 2 mmscf per day (six-month field average) in an oil field, and 3 percent of the daily volumetric feed gas flow rate of a natural gas field.

Processing business permit holders are not allowed to flare routinely. These companies must design refineries and processing plants without routine flaring.

For flaring due to gas commercialization issues, contractors must report their challenges to SKK Migas or the BPMA, along with plans to utilize gas (Article 10 of ESDM 17/2021). SKK Migas or the BPMA will review the contractors’ reports and submit recommendations to the minister (DG Migas), who will decide the status of the flared gas.

Development Plans

Article 2 of ESDM 17/2021 requires contractors and processing business permit holders to manage flare gas. Upstream contractors must prepare a flare gas management plan as part of field development plans. As per Article 17, contractors and processing business permit holders must submit their flare gas management plans to DG Migas every six months. The submissions must follow the format provided in the appendix of ESDM 17/2021. Article 15 enables contractors or processing business permit holders to flare or utilize flare gas collaboratively under the coordination of SKK Migas or the BPMA. This cooperation is intended to reduce the costs of individual companies and accelerate the mitigation of flaring. These collaborative activities must be reported to DG Migas.

Economic Evaluation

Article 3 of ESDM 17/2021 requires contractors and processing business permit holders to prioritize the utilization of flare gas. According to Article 4 of ESDM 17/2021, economic and technical studies must demonstrate that the utilization of low-combustion gas or gas with an impure gas share exceeding 50 percent is not feasible, and those volumes must be flared. Article 3 of ESDM 30/2021 requires contractors requesting a utilization of flare gas determination to provide technical, commercial, and financial documents and a copy of the price agreement with the flare gas buyer.

Measurement and Reporting

Measurement and Reporting Requirements

Article 11 of ESDM 17/2021 requires contractors or processing business permit holders to identify flared volumes. They can do so using measurement instruments, mass balance calculations, or other engineering calculations that follow good technical rules.

Measurement Frequency and Methods

Routine flaring operations must include measurement devices, unless contractors can demonstrate to SKK Migas or the BPMA that field economics are inadequate for their installation (Article 12 of ESDM 17/2021; see footnote 5). Mass balance or other engineering calculations are acceptable in case SKK Migas or the BPMA agrees with the contractor, but the contractor must install measurement devices if SKK Migas or the BPMA disagrees (Article 13).

Engineering Estimates

Entities that use mass balance or other engineering calculations must submit a report on the procedures employed to DG Migas. If irregularities in the report are found, DG Migas may require the installation of measurement instruments (Article 14 of ESDM 17/2021; see footnote 5). The flare gas management reports submitted to DG Migas every six months must include calculation procedures (Article 17).

Record Keeping

There is no obligation to maintain logs outside of the standard reporting requirements.

Data Compilation and Publishing

DG Migas receives gas flaring reports regularly and is known to be willing to share them upon request on a case-by-case basis. DG Migas does not formally or regularly publish flaring-related statistics.

Fines, Penalties, and Sanctions

Monetary Penalties

No evidence regarding monetary penalties could be found in the sources consulted.

Nonmonetary Penalties

Article 19 of ESDM 17/2021 calls for administrative penalties in case of noncompliance with these regulations (Article 19, Paragraph 1, lists specific clauses). Administrative penalties start with a written warning and escalate to cancellation of the appointment of the offending firm’s head of engineering if the written warning is not followed up within a month, and then to temporary suspension of production activities if the head of engineering remains in place after another month.

Article 10 of ESDM 32/2017 allows SKK Migas to revoke the flare gas allocation from the selected bidder if it fails to commence work within three months following the award or fails to start production within 12 months. However, there are no known cases of revocation.

Enabling Framework

Performance Requirements

The only performance standard identified is to start production and the utilization of flare gas within 12 months of the award date in the bid rounds conducted by SKK Migas (for gas being flared). There is no mention of an emission standard to be achieved.

Fiscal and Emission Reduction Incentives

No evidence regarding fiscal and emission reduction incentives could be found in the sources consulted. According to Article 20 of ESDM 17/2021 , the minister gives annual awards to contractors or processing business permit holders that optimize flare gas management. The award criteria is stipulated by DG Migas (Article 21).

Use of Market-Based Principles

ESDM 30/2021 calls for contractors to pursue the utilization of flare gas by signing agreements with flare gas buyers, processing business permit holders, or natural gas trading permit holders, which will use flare gas in commercial applications such as power generation fuels (e.g., compressed or liquified natural gas) (Article 2). Contractors must submit an application for flare gas utilization to SKK Migas or BPMA. The application must include documents on the flare gas source and the corresponding contracted volumes, the delivery point, contract duration, flare gas buyer and infrastructure descriptions, and a copy of the price agreement. Based on an evaluation of the bid parameters, SKK Migas or BPMA will make recommendations to the ESDM, which (through DG Migas) will approve or reject the application.

Negotiated Agreements between the Public and the Private Sector

No evidence regarding negotiated agreements between the public and the private sector could be found in the sources consulted.

Interplay with Midstream and Downstream Regulatory Framework

Several regulations relate to the transport and pricing of gas that is sold to other sectors further downstream (see section 3 of this case study). Downstream activities are supervised by a separate regulatory agency, BPH Migas. Article 31 of Government Regulation 36/2004 requires midstream and downstream license holders to make surplus facility capacity available to third parties, which would help integrate flare gas commercialization projects.