Policy and Targets

Background and the Role of Reductions in Meeting Environmental and Economic Objectives

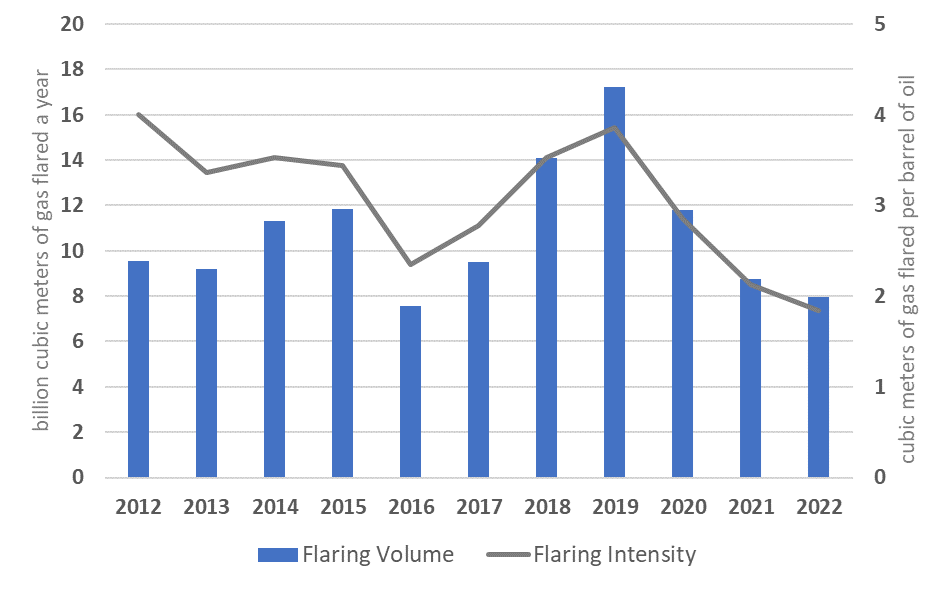

Crude oil production in the United States increased steadily between 2012 and 2022. It started to plateau around 2019, while both flaring volumes and flaring intensity started a significant downward trend as of 2019 (figure 1). Compared with 2012, the flaring intensity was about 54 percent lower in 2022. There were 4,229 individual flare sites in the most recent flare count, conducted in 2022.

Figure 1. Gas flaring volume and intensity in the United States, 2012–22

The United States endorsed the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 initiative in 2016. It also participates in the Global Methane Initiative and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition. In 2021, the United States rejoined the Paris Agreement and submitted a revised Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, setting a target for reducing its net economywide greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 50–52 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. The NDC does not mention flaring or venting, but reducing methane emissions from wells and natural gas pipeline systems is cited among the important actions the United States plans to take to control non-carbon dioxide GHG emissions.

The Federal Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) includes the Alaskan, Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, and Pacific regions. The western (beyond nine nautical miles of Texas waters) and the central (beyond three nautical miles of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama waters) planning areas of the Gulf of Mexico produce about 97 percent of all OCS oil and gas production. The share of federal offshore oil in total US production peaked at about 30 percent in 2009 and declined to less than 15 percent by 2020. The share of federal offshore gas in total gas production was about one-fifth throughout the 1980s and 1990s but started to decline in the early 2000s and fell below 3 percent in 2019.

In the 2010s, about 1.25 percent of the total OCS gas production was flared or vented, of which 70–80 percent was associated gas from oil wells. Of the gas flared and vented, 60–70 percent was flared, and the remainder was vented . With limited exceptions, flaring and venting have been prohibited in federal onshore and offshore oil and gas operations since the late 1970s, but several assessments by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the Department of the Interior and its offshore regulators over the years have found shortcomings in regulatory practice and technology implementation that may have prevented maximum possible reduction in the volumes flared or vented. For example, a 2010 GAO report found a large discrepancy between offshore operators, which reported flared and vented gas at 0.5 percent of gas production, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which estimated the share of flared and vented volumes at 2.3 percent. The GAO made several recommendations to the regulator to consider reducing the volumes flared or vented, including adoption of the best available technologies.

In 2011, the offshore regulator, Minerals Management Service, was separated into the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), to assess and manage offshore energy resources; the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), to regulate safety and environmental impacts; and the Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR), to manage royalty revenues. The GAO recommendations were addressed mainly by BSEE and BOEM. BSEE continues to pursue regulatory and technological options to reduce flaring and venting further while collaborating with BOEM on the economic viability of options. BSEE is responsible for regulating air emissions in offshore oil and gas facilities in the Gulf of Mexico.

In 2014, the President’s Climate Action Plan set a goal of cutting methane emissions from oil and gas operations by 40–45 percent from the 2012 level by 2025. In June 2016, the United States, Mexico, and Canada committed to reducing methane emissions from the oil and gas sector by 40–45 percent by 2025. Also in 2016, the EPA issued the New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) for new stationary sources of air pollution, including methane emissions from upstream and midstream oil and gas operations.

President Trump reversed some of these regulatory reforms with Executive Order 13783, Promoting Energy Independence and Economic Growth, 2017, which called for federal agencies to review and, as appropriate, revise or annul existing regulations that could burden the development of domestic resources. In 2020, the EPA rescinded significant portions of the 2016 NSPS, including methane emissions from oil and gas operations.

In early 2021, President Biden issued Executive Order 13990 on Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis, 2021. It directs all federal agencies to review all legal and regulatory rules issued by the previous administration and rescind or revise any that are inconsistent with the policy stated in this order. As a result, 2020 amendments are no longer in effect.

In November 2021, the White House issued the US Methane Emissions Reduction Action Plan, which included actions to reduce flaring and venting emissions by EPA, the Bureau of Land Management, and BOEM. In parallel, the United States, together with the European Commission, also launched the Global Methane Pledge, a voluntary commitment to reduce global methane emissions by at least 30 percent from 2020 levels by 2030.

On November 15, 2021, the EPA proposed the new NSPS rule, titled Standards of Performance for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources and Emissions Guidelines for Existing Sources: Oil and Natural Gas Sector Climate Review. EPA received 470,000 written comments on the proposed rule. In November 2022, EPA issued a supplemental proposal to address the comments and strengthen the 2021 proposal. The EPA issued its final rule on November 30, 2023, which will become effective 60 days after the date of publication in the Federal Register. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 introduced the Methane Emissions Reduction Program, which features a penalty. However, the U.S. Congress repealed the methane fee in February 2025.

Targets and Limits

Title 30 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) § 250.1160(a) defines limits within which gas can be flared or vented. For example, the amount is limited to what is necessary for its intended purpose, or an average of 50 thousand cubic feet (mcf) a day in any calendar month. The EPA’s proposed NSPS rule requires 95 to 100 percent reductions in methane and VOC emissions from various equipment such as pneumatic devices and storage vessels.

Legal, Regulatory Framework, and Contractual rights

Primary and Secondary Legislation and Regulation

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, 1953, is the overarching legislation governing offshore oil and gas activities and defining the federal role in regulating them. Title 43 U.S. Code § 1334(i) has prohibited flaring since September 18, 1978, unless the secretary of the interior finds that gas capture is not practicable or that flaring is necessary to alleviate an emergency or conduct testing or work-over operations. Title 30 CFR § 250.1160(a) defines limited conditions under which BSEE can approve flaring or venting. It issues guidance, primarily in the form of notices to lessees (NTLs), to clarify procedures and requirements for these approvals.

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, 1953, directs the Department of Interior to administer regulations for compliance with the National Ambient Air Quality Standards set in the Clean Air Act, 1970, which were amended in 1977 and 1990, to prevent significant damage to the air quality of any state as a result of offshore activities approved by the Department of Interior’s offshore regulator. The BSEE is responsible for ensuring compliance with the National Ambient Air Quality Standards in the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska. The EPA is responsible for air quality regulation in other federal waters under various programs of the Clean Air Act, 1990. The NSPS are issued and updated by the EPA under section 111 of the Clean Air Act. The NSPS has been modified several times since 2016; a new version is expected by the end of 2023 (see section 1 of this case study).

Legislative Jurisdictions

Federal laws govern flaring and venting in federal offshore fields, and national regulators regulate these practices. In state waters (within nine nautical miles from shore in Texas and three nautical miles elsewhere), state law regulated flaring and venting, and state entities regulate them.

Associated Gas Ownership

The federal government owns all oil and gas in the federal OCS. Energy firms access oil and gas in the OCS through concessions (leases) from BOEM . The concession grants the right to explore for and, if a commercial discovery is made, own, develop, and produce the oil and gas. Royalties are not paid on unavoidably lost gas, which includes flared and vented volumes under certain conditions (see section 21 of this case study).

Regulatory Governance and Organization

Regulatory Authority

The BSEE has the authority to regulate flaring and venting, including air emissions from them. The EPA has jurisdiction over offshore emissions as well.

Regulatory Mandates and Responsibilities

The Minerals Management Service was reorganized into BOEM, the BSEE, and the ONNR primarily to eliminate conflicts between managing revenues from oil and gas leasing and regulating safety and environmental aspects of offshore oil and gas operations within the same agency. Several reports by the Department of Interior’s Inspector General detail the close relationship between members of the royalty-in-kind program of the Minerals Management Service (terminated in 2010) and operators’ employees, the lack of resources limiting the ability of the Minerals Management Service to inspect an increasing number of offshore operations, and the industry’s practice of opposing potential Minerals Management Service regulations deemed uneconomic.

The BSEE is an independent regulator focusing on the safety and environmental aspects of offshore oil and gas operations, including flaring and venting. The BSEE, often working in coordination with BOEM, is also responsible for regulating air emissions from offshore oil and gas operations in the western and central Gulf of Mexico and the Alaska OCS Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. The BSEE’s Environmental Compliance Program ensures compliance with air emissions laws and regulations. BOEM requires air emissions monitoring and reporting plans. The Environmental Compliance Program also ensures compliance with those plans . The EPA regulates air emissions in all other federal waters.

Monitoring and Enforcement

The BSEE can conduct inspections and audits. Inspection procedures are intended to ensure compliance with Sections 1160 and 1163 of Title 30 CFR § 250. In 2015, the BSEE issued additional guidance on inspection procedures and the flaring or venting of low-volume flash gas from low-pressure equipment. Inspectors must verify operator calculations of flared and vented volumes, proper recording, and record maintenance according to standard operating procedures for measurement inspections. The BSEE requires inspectors to witness 10 percent of the accuracy tests for oil sales meters and 5 percent of the accuracy tests for gas meters.

The BSEE’s inspectors issue a document for an incident of noncompliance if an operator fails to prepare and maintain records for all gas flared or vented. Prompt notification is required if the inspector observes that the gas volume routinely flared or vented at a facility exceeds 50 mcf a day and the operator is unable to verify approval. The BSEE’s personnel in the Environmental Compliance Program can conduct risk-based offshore inspections to test that equipment that emit air pollutants is working correctly and that emissions levels comply with the National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

Licensing/Process Approval

Flaring or Venting without Prior Approval

Flaring or venting are permitted without BSEE’s approval under a limited number of circumstances, listed in Title 30 CFR § 250.1160(a) .

- when natural gas is used to operate production facilities or as an additive to burn waste products

- during the restart of a facility that had been shut in because of weather conditions, such as a hurricane

- during the blow-down of transport pipelines downstream of the royalty meter

- during the unloading or cleaning of a well, drill-stem testing, production testing, other well-evaluation testing, or the blow-down necessary to perform these procedures

- when equipment fails to work correctly during equipment maintenance and repair or when system pressure must be relieved

- when the equipment works properly but there is a temporary upset condition.

Authorized Flaring or Venting

An operator must receive approval from the BSEE regional supervisor to flare or vent natural gas, except in the circumstances specified above. Following the recommendations of the 2010 GAO report, the BSEE tightened the approval process, as communicated in NTL No. 2012-N04. This tightening led to a significant decrease in flare or vent approvals. NTL 2020-N04 supersedes previous NTLs on flaring and venting requests and states that the BSEE may approve flaring or venting on a case-by-case basis, with the following exceptions:

- The exception is in the national interest, such as when a major hurricane causes infrastructure damage. Bureau Interim Directive 2015-G070 requires that top BSEE management grant this exception.

- The operator claims that production from the well completion would likely be permanently lost if the well were to be shut in. According to Bureau Interim Directive 2015-G070, the BSEE’s resource conservation personnel must analyze necessary data from wells to confirm all such claims.

- The operator claims that short-term flaring or venting would likely yield a smaller volume of lost natural gas than if the facility were shut in and restarted later. According to Bureau Interim Directive 2015-G070, the BSEE’s resource conservation personnel must analyze necessary data from wells to confirm all such claims.

According to Title 30 CFR § 250.1161, approval for an extended period is possible but cannot exceed one year. The BSEE may approve requests for extended periods of flaring if the operator can demonstrate actions that will eliminate flaring and venting or demonstrates that lease economics do not support investment in eliminating flaring or venting.

According to the proposed EPA NSPS rule, flaring would be allowed only to eliminate venting of associated gas and only if the operator can demonstrate, as certified by a qualified third party, that it cannot access the market or use the associated gas in beneficial ways due to technical or safety reasons.

Development Plans

According to Title 30 CFR § 250.1160(b) , regardless of the exceptions, operators must not exceed the volume approved for flaring or venting in the Development Operations Coordination Document submitted to BOEM.

Economic Evaluation

Following the recommendations of the 2010 GAO report , the BSEE implemented pilot studies with infrared cameras and, jointly with BOEM, conducted a study on the economic viability of further reductions by adopting various technologies. As a result, the agencies decided not to extend capture requirements to lease-use gas sources, pending further studies. The BSEE and BOEM also analyzed data from Gulfwide Offshore Activity Database System. They concluded that “flaring currently vented methane and replacing high-bleed pneumatic controllers with zero- or low-bleed pneumatic controllers would likely provide the greatest opportunities for meaningful and cost-effective emission reductions.”

According to NTL No. 2020-N04 , the BSEE does not consider the avoidance of lost revenue as a justification for approving flaring or venting. For example, if gas production or transport infrastructure needs to be repaired and a well must be shut in during repairs, the BSEE will not allow operators to flare or vent gas to avoid shutting in the well and maintain the same pace of oil sales. Violations can result in civil or criminal penalties (see sections 18 and 19 of this case study).

Measurement and Reporting

Measurement and Reporting Requirements

According to Title 30 CFR § 250.1163, offshore facilities processing more than an average of 2,000 barrels of oil a day must install flare or vent meters. NTL No. 2012-N03 provides guidance on the BSEE procedures and requirements for installing meters. Measurements must be within 5 percent accuracy. Operators must use and maintain meters for the facility’s life. Meters must be calibrated regularly according to the manufacturer’s recommendation, or at least once every year, whichever is more frequent.

All hydrocarbons produced from a well completion, including all gas flared or vented and liquid hydrocarbons burned, must be reported to the ONRR on Form ONRR-4054 (Oil and Gas Operations Report [OGOR]), per Title 30 CFR § 1210.102. Since September 15, 2010, leaseholders must specify the volumes of gas flared and vented separately in OGOR Part B. They must use different disposition codes for flared oil-well gas, flared gas-well gas, vented oil-well gas, and vented gas-well gas. The 2016 GAO report found that the ONRR’s guidance on reporting emissions from lost gas, whether flared or vented, lacked specificity.

In reports, operators may classify gas used to operate lease equipment as lease-use gas. Where required, the amounts of gas flared and vented at each facility must be reported separately from that of facilities that do not require meters and separately from other facilities with meters. Flaring and venting from multiple facilities on a single lease or unit may be reported together.

Measurement Frequency and Methods

According to Title 30 CFR § 1210.102 , all operators must file Form ONRR-4054 for each well for each calendar month, beginning with the month in which drilling is completed, unless the well is for test production only or the ONRR grants written exemption. If any flaring or venting of gas required approval, operators must report to the BSEE regional supervisor the location, dates, number of hours, and volumes of gas flared, gas vented, and liquid hydrocarbons burned under the approval.

Engineering Estimates

According to Title 30 CFR § 250.1163 , offshore facilities processing less than an average of 2,000 barrels of oil a day do not have to install meters. Where meters are not required, gas flared and vented may be reported on a lease or unit basis. The BSEE does not prescribe estimation methodologies, but according to Title 30 CFR § 250.1203, the estimation method of gas lost or lease-use gas must be documented along with the data used.

Record Keeping

According to Title 30 CFR § 250.1163 , leaseholders must prepare records detailing gas flaring, gas venting, and liquid hydrocarbon burning for each facility and estimation methods used and maintain the records for six years. They must keep these records at the facility for at least the first two years; after two years, records must be available for inspection by BSEE representatives. At a minimum, the records must include the following:

- daily volumes of gas flared, gas vented, and liquid hydrocarbons burned

- the number of hours of gas flaring, gas venting, and liquid hydrocarbon burning, on a daily and monthly cumulative basis

- a list of the wells contributing to gas flaring, gas venting, and liquid hydrocarbon burning, along with gas-to-oil ratio data

- reasons for gas flaring, gas venting, and liquid hydrocarbon burning

- documentation of all required approvals.

Data Compilation and Publishing

The following data sources contain historical data on flaring and flaring volumes and GHG emissions associated with oil and gas production on the OCS:

- the Technical Information Management System

- the Gulfwide Offshore Activity Database System

- Oil and Gas Operations Reports Part A and Part B.

The first two databases are maintained by BOEM; the ONRR is responsible for the third. Following the recommendations of the 2010 GAO report , BOEM reconciled differences in reported offshore flaring and venting volumes between the OGOR and the Gulfwide Offshore Activity Database System.

There are other data sources on flaring and venting, all of them much less disaggregated than the above three. The Energy Information Administration makes available online data that include flared and vented volumes, aggregated by region. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, part of the Department of Commerce, uses US satellite technology to, among other things, monitor gas flaring activity around the world. The EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program requires reporting from large sources. The EPA publishes annual reports in the Inventory of US Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks that tracks US GHG emissions by source going back to 1990.

Fines, Penalties, and Sanctions

Monetary Penalties

Title 30 CFR Subpart N provides details on OCS civil penalties. The BSEE can impose such penalties if it determines that there is a violation (that is, a failure to comply with the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act [see footnote 20] or its implementing regulations, any other applicable laws, or the terms of leases, licenses, permits, rights-of-way, or other approvals, including those for flaring or venting).

The BSEE communicates the penalties, which are updated periodically, to operators. NTL 2023-N02 sets the maximum penalty of US$52,646 a day per violation, effective March 24, 2023. The NTL contains a matrix of three categories of violations from A to C, broadly increasing with the severity of safety or environmental impacts, resulting in three increasingly onerous government responses: warning, component shut-in, and facility shut-in. A warning for a category A violation has the lowest penalty, with an assessment starting point of US$19,685 a day per violation, but the actual penalty can drop below that. A facility shut-in enforcement for category C has the highest penalty, with an assessment starting point of US$48,640. If it is not paid, the facility can be shut in.

Failure or refusal to permit inspections or audits may be penalized by a fine of up to US$10,000 a day per violation (Title 30 CFR § 250.1460). An appeal can be made within 60 days by providing a surety bond equal to the assessed penalty amount or higher. Delayed payments without an appeal will accrue interest, late payment, and other applicable fees (Title 30 CFR § 250.1409).

The Methane Emissions Reduction Program includes a methane penalty as its central element, which starts at US$900 per tonne of methane in 2024 and increases to US$1,200 in 2025, and US$1,500 in 2026 and each year thereafter. The penalty applies to oil and gas facilities with annual methane emissions of at least 25,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. Companies were supposed to start paying penalties in 2025 based on the previous year’s emissions. However, in February 2025, the Congress repealed the methane fee.

Nonmonetary Penalties

Title 30 CFR § 250.1409 provides for further sanctions if penalties are not paid. They may include the cancellation of the lease, right-of-way, license, permit, or approval; the forfeiture of a bond; or the barring of the violator from doing further business with the federal government. The BSEE enforcement tools include component or facility shut-in if there is an immediate threat to safety and environment or operators fail to correct previously identified violations or pay assigned penalties.

Enabling Framework

Performance Requirements

US environmental law includes detailed requirements for flare design. Title 40 CFR § 60.18 provides general requirements for flares; other subparts include more details. Title 40 CFR § 63.987 requires a flare compliance assessment, provides certain technical details, and refers to other sections of the law for submitting flare compliance assessments (§ 63.999(a)(2)) and keeping records (§ 63.998(a)(1)). Title 40 CFR § 63.11 provides detailed performance requirements for flare design. For example, there should be no visible emissions, except for periods not to exceed a total of five minutes during any two consecutive hours; a flame should always be present; and the heat content of gas and the exit velocity must be calculated using the formulas provided in § 63.11. Taken together, environmental regulations require that flares be operated and maintained in a manner consistent with “good air pollution control practices,” typically interpreted to mean a combustion efficiency of 98 percent.

Title 40 CFR § 63.11 also provides alternative practices for monitoring leaks. Standard practices for monitoring leaks are provided in other parts of Title 40, including § 60, which apply to any stationary source subject to the NSPS, and § 61 and § 63, which apply to hazardous air pollutants. Appendix A-7 of § 60 details calculation methodologies for all regulated emissions, including volatile organic compound leaks, that are applicable for a diverse set of facilities.

The proposed EPA NSPS rule also has performance requirements such as continuous monitoring of the pilot flame. If a flare failure causes a “super-emitter” methane event, the operator is required to bring the flare into compliance promptly under the Super-Emitter Response Program.

Fiscal and Emission Reduction Incentives

If flaring or venting occurs without the required approval, or the BSEE regional supervisor determines that the operator was negligent or could have avoided flaring or venting, the hydrocarbons are considered avoidably lost or wasted and subject to royalties (12.5 percent in old leases, 16.67 percent in shallow waters, and 18.75 percent in deep water), according to Title 30 CFR § 1202. Operators must value any gaseous or liquid hydrocarbons avoidably lost or wasted under the provisions of Title 30 CFR § 1206. Fugitive emissions from valves, fittings, flanges, pressure relief valves, or similar components do not require approval under this subpart unless specifically required by the regional supervisor. The BSEE Resource Conservation Section is responsible for informing the ONRR about noncompliance with regulations resulting in a loss of hydrocarbons from flaring or venting that could have been avoided and the volumes involved.

Section 50263 of the Inflation Reduction Act declares that, for all federal leases issued after August 16, 2022, royalty is due on all produced gas except “(1) gas vented or flared for not longer than 48 hours in an emergency situation that poses a danger to human health, safety, or the environment; (2) gas used or consumed within the area of the lease, unit, or communi̬tized area for the benefit of the lease, unit, or communi̬tized area; and (3) gas that is unavoidably lost.”

Use of Market-Based Principles

No evidence regarding the use of market-based principles to reduce flaring, venting, or associated emissions from the Gulf of Mexico could be found in the sources consulted. There is no national carbon tax or market in the United States. The carbon dioxide cap-and-trade market in California covers oil and gas operations there. An increasing number of states are pursuing cap-and-trade markets, but typically not in states with large oil and gas production. The petroleum industry supports a carbon tax but not if there are also new methane and other emissions regulations.

Negotiated Agreements between the Public and the Private Sector

No evidence regarding negotiated agreements between the public and the private sector could be found in the sources consulted.

Interplay with Midstream and Downstream Regulatory Framework

The US natural gas market is highly liquid and gas infrastructure is vast. Most of the transport pipeline and storage infrastructure operate as regulated open access facilities. Federal and state regulators share responsibility in licensing midstream and downstream infrastructure and regulating open access (for example, setting pipeline tariffs). Pipelines that cross state boundaries are subject to the oversight of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Intrastate facilities are regulated by state regulators. Typically, independent midstream companies develop pipeline, processing, and storage facilities when they see an arbitrage opportunity to connect new production to consumers. Sufficient numbers of shippers or users must sign up for new capacity for midstream companies to justify investment. If midstream companies are not interested, it may be necessary for upstream companies, especially in offshore, to invest in pipelines. Delays in midstream infrastructure development have been a key reason for increased flaring in onshore upstream operations (see the case studies on Colorado, North Dakota, and Texas).

The policy of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for analyzing GHG emissions associated with gas pipeline projects has been uncertain since about 2016. Arguments for including emissions from upstream (oil and gas production activities that supply the gas) and downstream (use of gas carried by the pipeline such as power generation) in the commission’s review of pipeline applications have led to court cases and disagreements among commissioners. In early 2021, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, for the first time, considered GHG emissions associated with pipeline construction and operation during its review of a pipeline. This change in the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s pipeline approval criteria may have unintended consequences by delaying pipeline development and causing increased flaring or venting of associated gas.