Policy and Targets

Background and the Role of Reductions in Meeting Environmental and Economic Objectives

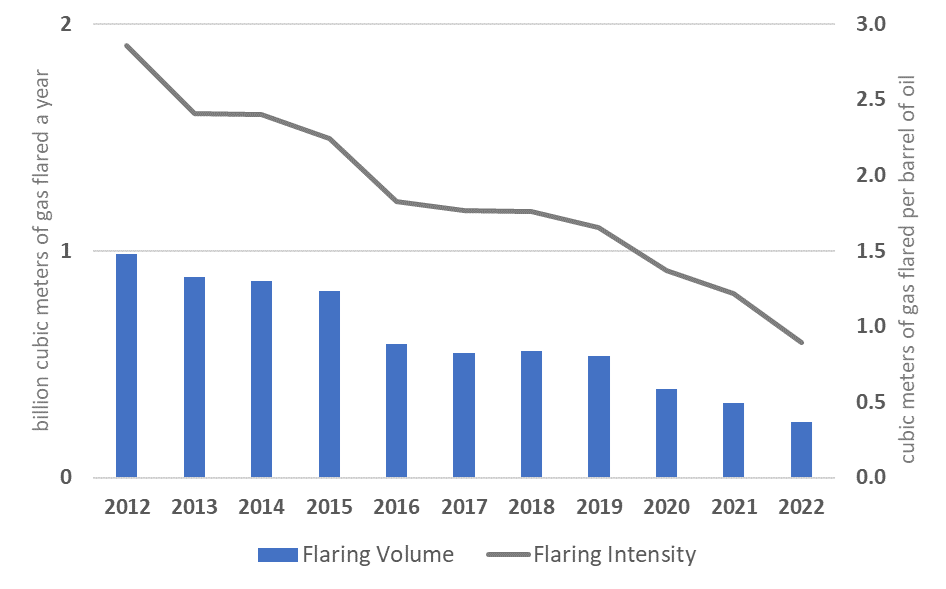

The volume of gas flared in Colombia declined by almost 70 percent, from 1 billion cubic meters in 2012 to 0.2 billion cubic meters in 2022 (Figure 1). Oil production also declined, but by only 21 percent. The flaring intensity declined steadily year after year during this period. There were 61 individual flare sites in the most recent flare count, conducted in 2022.

Figure 1. Gas flaring volume and intensity in Colombia, 2012–22

Following Ecopetrol, which endorsed the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 initiative, the government committed to the initiative in 2023. Colombia also participates in the Global Methane Initiative, the Global Methane Pledge, and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition. At the end of 2020, Colombia submitted an updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, increasing its commitment to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030 from 20 percent to 51 percent, albeit from a slightly higher business-as-usual-scenario emissions level. The new 2030 target for GHG emissions is 169 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e), down from 265 million tCO2e in the original NDC submitted in 2018. Many mitigation measures are proposed across all sectors of the economy, including reducing fugitive emissions across the oil and gas sector and using natural gas instead of coal, although flaring and venting are not specifically mentioned. The NDC includes methane capture from landfills and flaring or the use of the captured methane as a mitigation activity.

In 2010, Ecopetrol launched its current climate change strategy, which includes monitoring and reporting GHG emissions, reducing emissions from the company’s operations and supply chain, engaging in research and development, and contributing to the national climate policy. The company developed a work plan to reduce flaring by 8 million tCO2e by 2021 and carried out some projects to reduce methane leaks from its equipment. Ecopetrol is also seeking to reduce emissions from its operations by 20 percent by 2030 from the 2010 level. Emissions from flaring represent a small share of Ecopetrol’s emissions, but venting and fugitive emissions remain significant.

Over the past decade, re-injection of gas for enhanced oil recovery has decreased from more than 80 percent of gas volumes to about 50 percent, to increase the availability of natural gas in the domestic market. In August 2021, the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) released a new resolution for public consultation on the use, flaring, and venting of natural gas, and detection and prevention of fugitive emissions during upstream oil and gas activities. As a result, MME Resolution 40066/2022 was released on February 11, 2022 (updated in 2023 with MME Resolution 40317/2023), making Colombia one of the first countries to adopt specific regulation covering the control and reduction of fugitive methane emissions in addition to flaring and venting.

Targets and Limits

No evidence regarding targets and limits could be found in the sources consulted.

Legal, Regulatory Framework, and Contractual rights

Primary and Secondary Legislation and Regulation

Law 10/1961 explicitly prohibited gas flaring in production fields for the first time. MME Resolution 181495/2009 constitutes the main regulatory framework for exploring and producing hydrocarbons, with the objective of maximizing their recovery and avoiding waste. Articles 52 and 53 prohibit gas flaring and the wasting of gas. The oil and gas sector is subject to all regulations pertaining to environmental protection and sustainability as well as consultation requirements with communities, health and safety requirements, and labor conditions. MME Resolution 40687/2017 establishes technical standards for offshore hydrocarbon exploration projects and regulates gas flaring and venting for these activities.

MME Resolution 40066/2022 updates provisions for flaring, venting, and fugitive methane emissions. Operators, in accordance with the provisions of the competent environmental authority within the framework of an environmental license, can flare the gas recovered on the surface as a result of well control operations and initial production tests during the development of exploratory drilling. Venting is banned in both exploration and production, but exceptions are granted during an emergency or for maintenance. Additional rules also cover fugitive methane emissions by establishing requirements for leak detection, measurement and repair, technical inspections, and monitoring. For all instances relating to flaring and venting, the respective provisions in MME Resolution 40066/2022 derogate those in MME Resolution 40687/2017 and MME Resolution 181495/2009. Based on the experience gained since 2022, MME Resolution 40317/2023 introduces a number of adjustments to Resolution 40066/2022. The most important ones involve baseline volume definitions, reporting requirements, and technical standards to be applied.

Decree 1056/1953, Petroleum Code, was last amended in 2009. Further regulations have updated aspects relating to contracts, royalties, and fines, but the Petroleum Code provides key regulatory guidelines for the oil and gas industry. There are three contract types for the exploration and exploitation of oil and gas:

- production-sharing contracts (PSCs), known as association contracts, with Ecopetrol

- technical evaluation contracts

- exploration and production contracts entered into with the National Hydrocarbon Agency (Agencia National de Hidrocarburos [ANH]).

Regulations are issued by the MME; the ANH defines rules for technical evaluation and exploration and production contracts.

Law 23/1973 defines the rules for pollution and environmental liability and authorizes the enactment of the Colombian Natural Renewable Resources Code, Decree 2811/1974. Law 99/1993 defined Colombia’s environmental institutional framework, the National Environmental System, and introduced environmental licensing. Decree 1076/2015 compiles all the environmental rules applicable to the oil and gas sector, including those in Decree 2041/2014 relating to regulatory requirements for unconventional reservoirs and the new terms applicable for the environmental licensing processes.

Legislative Jurisdictions

Gas flaring and venting are matters of national jurisdiction.

Associated Gas Ownership

Article 332 of the Political Constitution, 1991, vests the subsoil and any nonrenewable natural resources in the state. In 2003, association contracts with Ecopetrol were replaced with exploration and production contracts, which apply the same principles as the tax-and-royalty regime or concessions. Technical evaluation contracts allow evaluation of an area for up to 36 months, but no exploitation is allowed. If exploratory and appraisal drilling leads to production, the company is not authorized to sell it but can obtain an exploration and production contract to start exploitation. These contracts grant companies the exclusive right to explore and exploit oil and gas in a defined area. Companies have rights to all oil and gas production or the volumes remaining once royalties have been paid in kind. Companies can dispose of oil and gas production freely by negotiating with buyers in local or international markets.

Article 14 of Law 10/1961 requires all operators, privately or state owned, to avoid wasting any gas produced. Operators should sell gas, re-inject it in the field for future use, or use it to enhance oil recovery. If the operator does not stop wasting gas within three years, the government has the right to take the ownership of gas free of charge and ensure its utilization by building the required infrastructure.

Regulatory Governance and Organization

Regulatory Authority

Ecopetrol controlled the development of hydrocarbon resources until Presidential Decree 1760/2003 introduced two essential changes in the Colombian petroleum industry:

- creation of the ANH as a special entity in charge of administering and regulating hydrocarbons in Colombia (later, Decree 4137/2011 modified the legal status of the ANH and converted it into a state agency)

- transformation of Ecopetrol into a partially state-owned company (Law 1118/2006) dedicated to upstream, midstream, and downstream oil and gas activities within and outside of Colombia, governed by the applicable private law.

The ANH is under the MME. It has a distinct legal status and enjoys administrative and financial autonomy. Ecopetrol became another company in the market, leaving the sole regulatory and administrative management of hydrocarbons to the ANH. ANH oversees all contractual oil and gas arrangements except for the association contracts Ecopetrol held as of December 31, 2003.

Decree 70/2001 grants powers to the MME as the principal governing body responsible for upstream oil and gas operations. Accordingly, MME Resolution 181495/2009 updated by Resolution 40098/2015, establishes that the MME is responsible for issuing any technical rules and administrative decisions associated with the regulation and imposing applicable sanctions for noncompliance. With Resolution 180877/2012, the ANH and MME executed an interadministrative agreement that delegated certain inspection functions and regulatory activities to the ANH.

When an environmental license is required, it may be granted only at the national level by the National Environmental Licensing Authority (Autoridad Nacional de Licencias Ambientales) in accordance with Decree 1076/2015 .

Regulatory Mandates and Responsibilities

The ANH grants flaring authorizations, sets measuring standards, and monitors compliance (see sections 9, 10, 13, and 14 of this chapter). The Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development is the highest environmental authority in Colombia, responsible for the environment and renewable natural resources management. It regulates the environmental impact of Colombia’s oil and gas operations. Regional environmental agencies have the right to issue regulations, but they must align with the ministry’s national regulations and the National Environmental Licensing Authority’s licensing. The environmental license should be obtained before the initiation of a project, work, or activity.

Monitoring and Enforcement

Decree 1760/2003 empowers the ANH to implement the measures necessary to monitor, enforce regulations, and audit the activities related to the oil and gas industry. Audits focus primarily on items such as control mechanisms, compliance with regulation, and reporting, including matters specific to flaring.

The National Environmental Licensing Authority has the power to impose sanctions on transgressors of environmental regulations and licenses. In the case of offshore activities, the maritime authority and the environmental investigations institute also play a prominent role.

Licensing/Process Approval

Flaring or Venting without Prior Approval

Article 6 in MME Resolution 40066/2022 allows flaring during the exploration phase for testing purposes. Article 25 bans all venting during exploration except for safety and as part of drilling activities. Article 30 bans all venting during production. Article 34 cites safety and maintenance as the main reasons for exceptions. In all instances, the vented volumes and the underlying reasons for venting need to be reported.

Authorized Flaring or Venting

Any activity or operation undertaken by the operator as part of an oil and gas contract requires the relevant documentation and forms to be filed with the MME for it to approve and control the applicable activity.

Article 10 in MME Resolution 40066/2022 requires a flaring authorization during the production phase. Article 18 provides the details required for a flaring authorization. Specific requirements for routine flaring are stipulated in Article 11, and for unforeseeable events, Article 19 provides for situation-specific flaring authorizations.

ANH Circular 18/2014 on gas control and flaring specifies that all requests to flare should be submitted in writing to the ANH. The ANH authorizes the gas volume, time of flaring, and whether the gas flared should be subject to royalty.

Development Plans

Articles 31–33 in MME Resolution 40066/2022 requires new projects to be designed to capture vented gas. Existing projects have to upgrade their facilities for capture or flaring of otherwise vented gas within the required timeframe of two years.

Economic Evaluation

Article 52 of MME Resolution 181495/2009 details possible flaring exceptions in cases where gas capture is not economically viable. The operator must justify that gas capture is uneconomic, and the MME must approve the justification.

For routine flaring, Articles 11 and 16 in MME Resolution 40066/2022 reaffirm the above approach for gas that cannot be produced economically viable.

Measurement and Reporting

Measurement and Reporting Requirements

MME Resolution 41251/2016 regulates the measurement of the volume and quality of the hydrocarbons for the purposes of paying royalties. Article 17 states that the volume of gas used in a facility for artificial lift or injection, consumption in operations, power generation, and flaring should be measured. All flaring should have received prior approval from the ANH. ANH Circular 18/2014 states that operators should report the volumes of total gas produced; associated gas used for generating electricity, running compressors, or re-injection; and gas flared within the first seven days of each month. Articles 28, 29, and 30 in MME Resolution 40066/2022 require reporting of gas being vented and Article 38 requires the quantification of gas captured to avoid venting. Intentional venting during exploration must be reported daily; the data will be consolidated in monthly reporting via Form 30 DH (Article 29).

Measurement Frequency and Methods

MME Resolution 41251/2016 covers measurement frequency and methods. Article 7 states that the quality of gaseous hydrocarbons should be determined by establishing the density, composition, and calorific value. For the official measurement points, monthly analysis of hydrocarbons with up to 12 carbon atoms using gas chromatography should be performed. Quality tests should be carried out on representative samples taken at official sampling points using Section 14 of the latest version of the American Petroleum Institute’s Manual of Petroleum Measurement Standards. Article 17 states that all gas produced should be continuously measured. A daily log of physical and electronic data should be kept per the American Petroleum Institute’s Manual of Petroleum Measurement Standards.

In the late 2010s, the Comptroller General of the Republic (Contraloría General de la República), the auditor of the ANH, investigated whether the ANH was adequately enforcing natural gas production measurement and whether the information provided was transparently disclosed with easy and user-friendly access. The Comptroller General of the Republic concluded that the data and the disclosure procedures conformed to industry best practices and were managed in a timely, comprehensive, and reliable manner.

Engineering Estimates

Section 3 of MME Resolution 41251/2016 states that methods other than direct measurements, such as engineering estimates, may be used to fulfill measurement requirements in special cases and with prior authorization from the supervisory authority. Section 29 requires a description of the volumetric and mass balance equations of liquid oil, water, and gas and field facilities highlighting the consumption, estimated losses, re-injection and gas flared, and equipment used for their determination and quantification. Descriptions should be provided separately for initial tests, extensive testing, and commercial production.

Record Keeping

Article 27 of MME Resolution 41251/2016 requires operators to implement a measurement quality management system in accordance with Colombian Technical Standard NTC-ISO 10012, Management Systems for Measurement, 2003. Article 28 of the resolution details the logging of daily measurements. Operators should prepare a digital or physical log of daily control activities, audits, calibrations, training, verifications related to the official measurement, and production inspection at wellheads. Subsection 6 requires operators to keep records containing the information necessary for operating the measurement management system.

Data Compilation and Publishing

The ANH publishes annual management reports on its website. They include data on gas flaring and the authorizations granted.

Fines, Penalties, and Sanctions

Monetary Penalties

MME Resolution 181495/2009 establishes fines specific to gas flaring and venting. According to Article 52, operators must pay royalties on flared, vented, or otherwise wasted gas unless an exception was obtained from the ANH. Article 64 imposes a fine of up to US$5,000 on any violation, in accordance with Article 67 of the Petroleum Code . Article 82 in MME Resolution 40066/2022 confirms that the sanctions for infringement of its rules are those in Article 21 of the Petroleum Code and Article 67 of Decree 1056/1953 . Article 26 of Law 1753/2015 states that the MME may impose fines of 2,000–100,000 times the legal monthly minimum wage for each breach of the obligations established in the Petroleum Code. The ANH may impose fines in case of a breach of any of the contracts it oversees, up to the value of the unfulfilled activity if the obligations have associated monetary values. If they do not, the ANH can impose a fine of up to US$50,000 for the first breach. Each subsequent breach will result in a fine up to the smaller of twice the amount initially imposed or the value of the contract’s guarantee.

Nonmonetary Penalties

Upon expiration of the terms indicated by the ANH for the payment of fines or the fulfillment of the obligations breached by the contractor, the ANH may terminate the contract if the contractor has not fulfilled its obligations. Article 11 of the Petroleum Code, 1956, states that any difference of fact or a technical nature that may arise between the interested parties and the government on the matters dealt with by the code that cannot be resolved amicably will be submitted to the opinion of three experts, one selected by the government, one by the interested party, and one by a third party. Article 68 states that the government may terminate any contract or cancel a license granted if a dispute is decided in the government’s favor.

Enabling Framework

Performance Requirements

Article 22 of MME Resolution 40066/2022 (as revised in 2023, see footnote 3) requires operators to comply with flare efficiency standards, which, along with other technical and reporting requirements, will be developed by the regulator by the end of October 2023. Operators must have their flares inspected and results reported within 12 months of the issuance of the technical guidelines. Inspections can be done by entities approved by the regulator or international accreditors. All flare volumes must be reported monthly via Form 30 DH (Article 24).

Title 5 (Articles 42–49) of MME Resolution 40066/2022 (revised in 2023) focuses on natural gas (methane) leaks. Article 42 requires operators to identify and quantify the leaks. Article 43 lists instruments that can be used for detection of leaks and quantification of leaked volumes; and allows for approved engineering calculations in exceptional cases. The instruments must measure concentrations equal to or greater than 500 parts per million. A baseline of leaked volumes must be established for all facilities and all equipment and components covered in this resolution. The regulator may inspect and audit the facilities to ensure accuracy and compliance (Article 49). Title 6 provides detailed instructions on leak detection and repair. Article 50 states that the required leakage elimination program needs to cover at least 95 percent of all leaking gas.

Fiscal and Emission Reduction Incentives

No evidence regarding fiscal and emission reduction incentives could be found in the sources consulted.

Use of Market-Based Principles

In May 2017, at the One Planet Summit in Paris, Colombia joined Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Mexico, and the US states of California and Washington and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec in launching the Carbon Pricing in the Americas Cooperative Framework. Law 1931/2018 established the National Program of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Tradable Quotas, a national emissions trading system (sistema de cupos y créditos), which is still awaiting implementation.

Negotiated Agreements between the Public and the Private Sector

No evidence regarding negotiated agreements between the public and the private sector could be found in the sources consulted.

Interplay with Midstream and Downstream Regulatory Framework

Since its establishment under Laws 142/1994 and 143/1994, the Commission on Regulation of Energy and Gas has been the principal regulatory body responsible for regulating gas transport and commercialization. It regulates energy and gas activities to ensure the availability of efficient energy and appropriate competitive structures that prevent companies from achieving dominant positions. Gas regulations encompass aspects ranging from contractual relations and technical standards to transport conditions, sale terms, distribution, and consumption. The Unified Transportation Regulation, outlined in the Commission on Regulation of Energy and Gas Resolution 071/1999, establishes open and nondiscriminatory access to natural gas pipelines.

MME Resolution 40066/2022 requires development of a program to eliminate fugitive methane emissions in upstream operations and other parts of the value chain, such as storage facilities.